Restoring Pugliese: Tango’s Transitional Years and the Vision Behind TangoSparks

An Essay on 1949-50 and Interview with Frank Jin

1. A World Restored

Let me begin by briefly situating TangoSparks, the new label launched this year by Beijing’s Frank Jin.

The digital restoration of Argentine tango entered the 2020s with cautious optimism. For the first time, skilled teams in Vienna, Brussels, and elsewhere began delivering consistent, high-fidelity transfers of core repertoire spanning the early 1930s to the late 1950s. These efforts helped close long-standing gaps in the Golden Age canon—correcting pitch, compensating for studio microphone placement, and rescuing dozens of orchestras whose recordings had circulated for decades in muddled or overly filtered form. The benefits extended beyond the Big Four to include at least fourteen other key orchestras.1 Among them, the restorations of Troilo, D’Arienzo, Biagi, Laurenz, and Demare stand out for their fidelity, improved pitch calibration, and their impact on the dance floor.2

Since that initial surge, the field has entered a more mature phase. Leading engineers continue to refine their methodologies: sourcing cleaner shellacs and early vinyls, adjusting reference pitch toward historically plausible baselines, and assembling composite transfers from multiple discs to mitigate uncorrelated wear. Their discographic annotations now serve as indispensable references. Yet several problems remain.

One is familiar. Despite steady advances in tracking, alignment, and equalization, the problem of surface noise in shellac-era recordings persists. Thoroughly removing hiss, hum, and crackle without compromising signal integrity and regressing to the heavily filtered sound of the early digital era remains a difficult technical frontier—one likely to require further progress in neural-network-based denoising before a definitive solution emerges.

A second problem dating to approximately 1949-53 is less widely recognized. Structural defects introduced during the chaotic early years of microgroove mastering and vinyl LP production remain largely uncorrected.3 Many recordings from this transitional period were mastered using ad hoc methods not yet fully adapted to the geometry and dynamics of the new format. Subtle distortions of pitch, phase, and tonal balance were often embedded at the production stage and carried forward unaltered in subsequent releases. These were not random flaws accrued through wear but systematic artifacts—unintended consequences of an industry rushing toward higher fidelity with tools not yet equal to the task. Mastering chains were in flux. Quality control was uneven. Correcting the resulting errors requires more than pristine discs; it demands historical knowledge, technical precision, and sharp musical acuity.

This is the context in which I assess Jin’s new project. Best known for his discographic research and knack for locating definitive performances buried in labyrinthine CD releases, Jin now turns his attention to the transitional years of microgroove masters and early LPs. Some of the recordings he restores are innovative pieces that are well-suited for social or exhibition settings, but arguably remain underappreciated due to subtle mastering defects and transfer flaws. Others are beloved standards, where marginal gains in ensemble clarity and tonal coherence justify the effort. His method draws on historical expertise, absolute pitch, prior work at a leading restoration boutique, and a novel technique he terms portionized mixing. What follows examines these early releases in context—comparing them to the strongest existing alternatives, and using them to explore the musical and historical dimensions of Pugliese’s output during the transitional years.

2. Debut of TangoSparks

The debut TangoSparks series refreshes Pugliese’s output from 1949 to 1950, a period marked less by the orchestra’s transcendent sound than by its intense and often volatile spirit. These recordings are not universally loved.4 Many dancers and DJs prefer the melodic beauty and clear structures of the 1943–47 period, when the orchestra’s arrangements drew from the mythic sound of tango’s great stylists—the De Caro brothers, Laurenz, Pedro Maffia, Eduardo Arolas, Salvador Grupillo, Virgilio Expósito, and Agustín Bardi. By contrast, the recordings the late ‘40s are more abstract, denser, and darker—not quite brooding, but temperamental. If the melodies of the early ‘40s evoke the bright precision of the painter Wassily Kandinsky, then those of the late ‘40s reflect the jagged layers of Georges Braque.

This, without doubt, is part of their appeal. These songs register the strain and defiance of dark years after 1946, when mounting repression under Juan Perón’s newly consolidated regime weighed heavily on artists, especially dissident Marxists such as Pugliese who watched as his vision for Argentina’s future, once-solid, melted into air.5 The suffering extended inward as well: Morán later described the orchestra’s internal culture during this period as rivalrous and Pugliese himself as a cruel leader, with tension over the group’s equitable compensation plan becoming a point of controversy. When quitting the orchestra for good in March 1954, Morán described it as a “rotten apple.”6

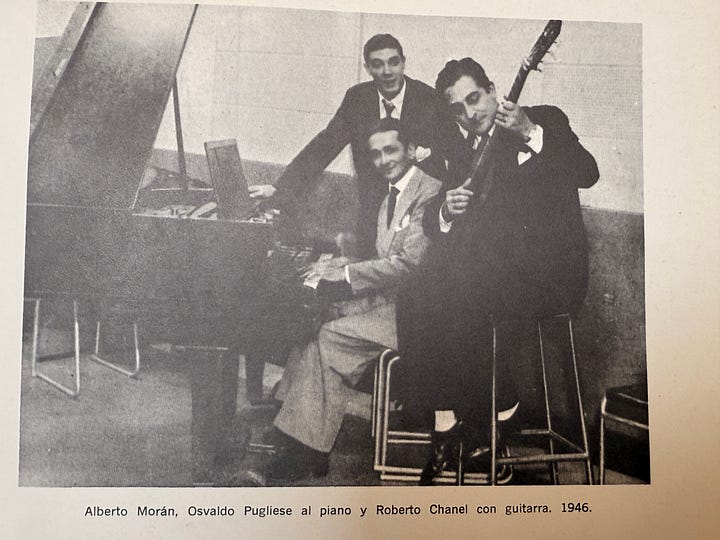

The emotional shift is palpable. For dancers attuned to the phrasings of El remate, Tiny, and Farol, of Flor de tango, El taita, and Fuimos, the 1949-50 recordings offer something different. As Troilo and Piazzolla pursued new heights of refinement, Pugliese poured out something raw from the other side of the river. He was fortunate to have great musicians by his side to summon the harmonies that distinguished the group in this era. Balancing the force of the bandoneóns and singers were four talented violinists: Enrique Camerano, Oscar “Cacho” Herrero, Julio Carrasco, and a promising new hire in 1949—Emilio Balcarce, who would assume responsibilities for some of the new arrangements in these transitional years.7

For all their power and intrigue, many of these performances remain rarely played. If they were ever standard fare, I’ve yet to hear it. Their obscurity probably owes as much to pitch and equalization flaws that have persisted for decades as to the fact that some dancers find them hard to read.

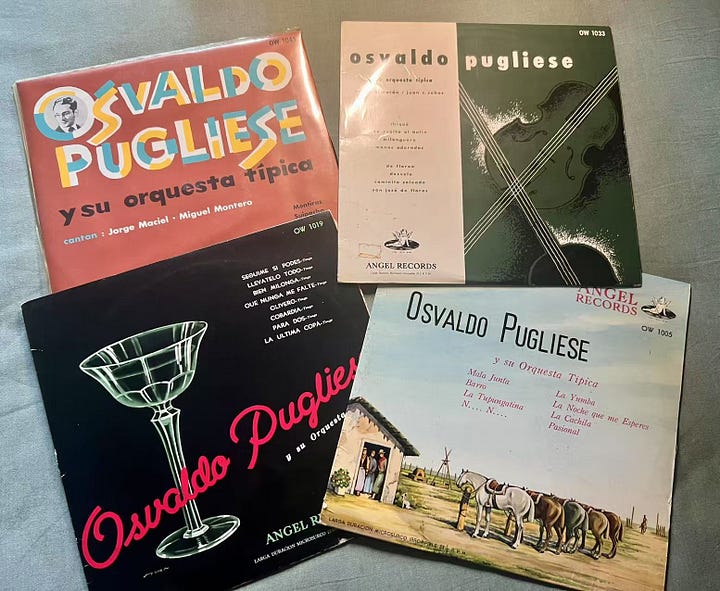

Existing transfers of Pugliese’s output in these years fall into three main categories. First are CD editions from Odeón and its corporate successors.8 When original masters were still intact, these teams enjoyed privileged access—not only to the metal parts themselves, but also to original production notes and high-grade studio equipment.9 Yet during the 1988–2005 reissue period, not all transfers drew from first-generation sources. Many relied on worn shellac or vinyl pressings, or on second-generation masters copied to degradable, non-metal media. The results were mixed. Pitch drift, tonal imbalance, surface noise—and the heavy-handed denoising typical of 1990s restoration—were common. Compression artifacts also appear in some tracks. Today, these CDs are mostly out of print and incresingly hard to find in mint condition.

Second are reissues from gray-market CD labels in Argentina and Europe, alongside restorations by a growing list of collectors in Argentina Japan, Germany, and Canada. These often sound no better than the official releases, despite being widely distributed and often encountered on streaming platforms.

A third category comprises the digital restorations from Tango Time Travel10 in Brussels and TangoTunes in Vienna11 —projects that source shellacs and early LPs and apply modern techniques with a level of care previously unseen. A fuller analysis of these contributions appears elsewhere on this blog. These restorations mark a decisive improvement over earlier releases. Yet even these retain traces of transitional-era mastering artifacts such as pitch skew and tonal haze, or where shellacs served as the source, heavy groove noise.

The historical and technical context is key. Pugliese’s 1949–1952 sessions took place during a volatile phase in Argentina’s recording industry, as studios shifted from shellac to vinyl and began experimenting with magnetic tape, acetate, and other mastering intermediaries. Techniques and standards were in flux. Equipment upgrades were piecemeal, often improvised. Many sessions were produced using gear not yet calibrated to the new formats. As a result, subtle but persistent flaws were embedded during production itself, and then passed down through both analogue and digital reissues.

These limitations help explain why some of Pugliese’s best recordings remain absent from regular rotation. Instrumentals from 1943 to 1953 are frequently heard in social and competitive settings. Yet standout recordings from 1949 and 1950—such as Catuzo, Chuzas, Pinta Brava, El Tobiano, Pastoral, Bien compadre, Don Aniceto, and Canaro en París—are rarely played, despite their clear kinship with tangos such as De floreo, Negracha, Patético, Malandraca, Jueves, El buscapié, and the 1947 take of N.N.12 Jin’s first release restores many of these works in full for the first time.

A standout is De floreo, composed by Carrasco with a little help from Ruggiero, and recorded on March 29, 1950. De floreo is a tango that, since the 1990s, has almost certainly been danced or performed somewhere in the world each night.13 Jin’s edition restores the recording’s harmonic center and instrumental texture. Pitch is more stable and accurate, particularly in Ruggiero’s opening solo for bandoneón and the signature obbligato for Camerano’s bow—both of which sound more centered here than in any prior release.14

The most widely circulated versions draw on source materials that differ in format, fidelity, and the compromises they entail. TangoSparks and Tango Time Travel rely on LDS 136, a 1953 Odeón LP released after the studio’s transition to tape mastering—completed, for Pugliese’s orchestra, by October 1952.15 The LP’s low surface noise and extended dynamic range yield a more polished signal, and the Tango Time Travel edition is remarkably clear. Yet the original master was a metal disc cut for pressing to 78 rpm shellac, and the format mismatch with 33 rpm vinyl meant that an intermediate mastering chain was almost certainly required. These extra steps created room for small but audible defects in equalization or phase.

TangoTunes, by contrast, bypasses LP-era mastering entirely. Its edition is based on a shellac pressing of matrix 17601-30610 cut directly from the original metal parts.16 But there is a tradeoff. De floreo was a popular release, circulated widely, and played often. The particular disc used by TangoTunes bears the marks of its success: heavy groove wear, persistent crackle, and a noticeable veil over the higher frequencies. Its transfer may preserve more of the session’s original character, but is covered by a heavy and distracting patina of sound.

For decades, the most familiar editions of De floreo came either from the compact disc Instrumentales Inolvidables Vol. 2 released by EMI Odeón under the Reliquias label in 1999, or from Edición Aniversario 1905–2005, issued six years later.17 These official transfers, evidently sourced from shellac discs rather than masters, reflect the limitations of late-20th-century digitization practices in Argentina. The pitch runs high, playback is slightly fast, and the equalization seems mismatched, likely defaulting to a generic curve instead of the one used by Odeón in the late ‘40s. Most disruptive, however, are the mechanical faults: in several passages, the audio momentarily skips, clipping notes and breaking the musical flow. These glitches likely stem from mistracking during transfer—caused by a worn or ill-matched stylus, misapplied tracking force, or the simple inattention of studio engineers. Alternatively, overzealous denoising software from the 1990s could be to blame. In either case, the result is not unlistenable, but one of tango’s finest instrumentals arrives disfigured.

These scars are especially damaging in a piece that relies on contrast. The arrangement pivots on the staccato snaps of the bandoneóns striking against suspended violin lines. The EMI Odeón editions blur that dialogue. Even casual listeners can hear the problems. For choreographers, teachers, and milongueros—who may return to this track dozens of times each year across decades—the distortions are tragic. The damage is audible, for example, in two otherwise beautiful performances: Milena Plebs and Ezequiel Farfaro dancing in Buenos Aires in 2004 [video] and Laura D’Anna and Sebastián Acosta, filmed in Brussels in July 2017 [video]. By contrast, the restored clarity of the Tango Time Travel edition comes through vividly in Virginia Gomez and Christian Márquez’s March 2025 exhibition in Istanbul [video], and in a July 2022 performance by Stephanie Fesneau and Fausto Carpino in Poland [video].

The classic Malandraca also receives a long-overdue facelift in Jin’s edition, with markedly improved pitch calibration and restored ensemble texture. The gains are especially evident in this piece, relentlessly propelled by pounding bandoneóns and Pugliese himself, ricocheting notes like dice through the European concert grand of Odeon’s studio on Avenida Córdoba.18 Over it all, ethereal violin tuttis stretch like silk threads, anchored by the bowing of contrabajista Aniceto Rossi. Suspense builds with the measured pace of Russian roulette.

Among professional performers and choreographers, Malandraca ranks among the most favored of Pugliese’s instrumentals—performed by nearly a hundred artists since 1999 and repeatedly chosen for its drama and force.19 Yet until now, none of its available transfers have done it justice. The official CD editions from EMI Odeón are badly mis-pitched and excessively fast, clocking in at 2:52. The TangoTunes edition, sourced from a shellac matrix, errs in the opposite direction: too slow at 2:58, and veiled by a heavy patina of surface hiss, the strings unnaturally muted.20 Perhaps for that reason, it has yet to be featured in any public exhibitions—at least none known to me. The distortions in the now-obsolete CD version are plainly audible in many otherwise superb exhibitions—most notably in the June 2012 Montreal performance by Milena Plebs and Pablo Pugliese [video], and in the September 2023 show by Delfina Pissani and Diego Martín Valero in Buenos Aires [video].

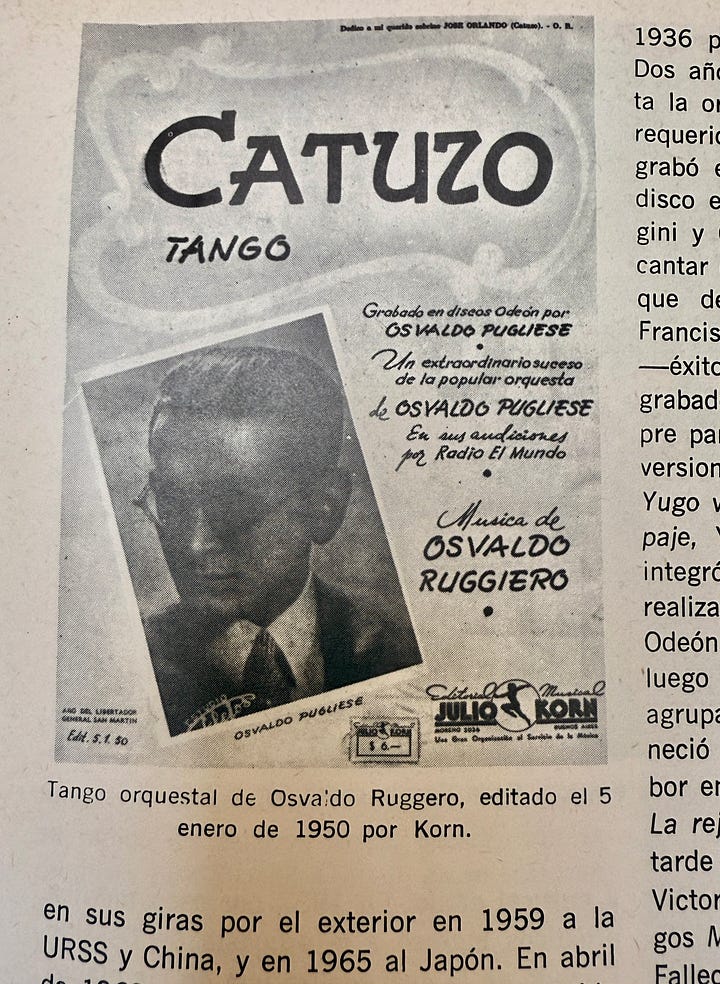

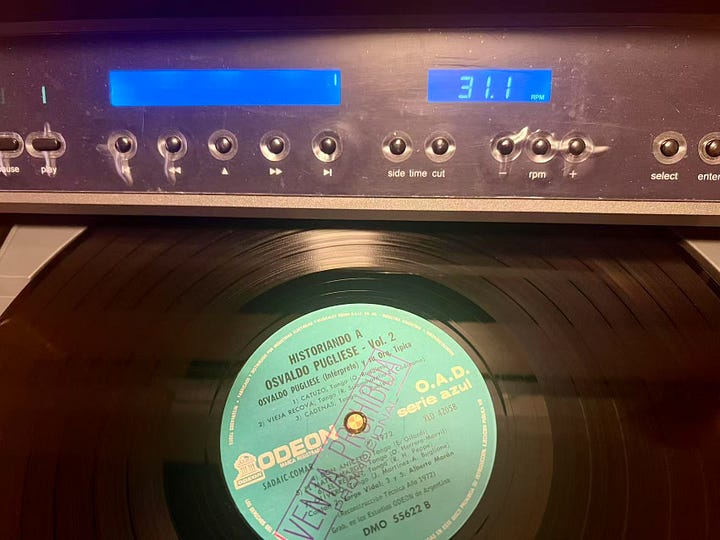

Another highlight is Catuzo, an incandescent instrumental composed by Ruggiero in the same idiom of “rhythmic preponderance” that shaped La yumba and Negracha.21 The piece was recorded in the closing days of 1949—the city’s streets would have been sweltering, the studio’s metal fans whirring in vain, the approach of Christmas promising respite from the city’s relentless cabaret calendar. Today, Catuzo is something of a lost treasure. Upon release, it was hailed and actively promoted by publisher Julio Korn. It ignites like a match from the start, and its climactic variación for bandoneón foreshadows the one closing the 1955 recording of Emancipación. Yet for decades, Catuzo was sidelined—circulating only in legacy CD transfers marred by mis-pitching, incorrect equalization, and muffled tone.

One such version, likely from an EMI Odeón CD, is clearly audible in a remarkable March 2019 exhibition by Jonathan Saavedra and Clarisa Aragón [video], which appears to be the first ever recorded.22 A recent TangoTunes edition—based on Historiando a Osvaldo Pugliese, Vol. 1, a 1972 vinyl release—helped reintroduce the piece to connoisseurs, prompting a March 2023 studio improvisation and a subsequent performance that September in Buenos Aires by Aldana Silveyra and Diego Ortega [the March video; the September video].23 While the TangoTunes release is remarkably good, Jin’s edition easily surpasses it, offering tighter equalization, subtle pitch correction, and significantly improved clarity.

A final jewel in the set is Canaro en París, a theme immortalized in recordings by D’Arienzo, De Angelis, Varela, Salamanca, Quinteto Real, and Canaro himself. In Pugliese’s 1949 treatment, however, the piece is reconceived. The arrangement privileges lyrical string phrasing and features a hypnotic exchange between Rossi’s contrabajo and Ruggiero’s bandoneón—a dialogue rarely heard in Golden Age tango. Most striking is Rossi’s performance, which his son Alcides later described as a “solo variación a cappella”—a genuine rarity in the genre, and quite possibly the first ever captured on record.24 The emphasis on melody, and the tension between intensity and restraint, suit the musicality and dynamic control now favored (and increasingly taught) by dancers such as Saavedra and Aragón.

Vocal recordings from this period have received comparatively little attention. Most DJs continue to favor Morán’s better-known 1945–47 tangos; tracks like El abrojito, Yuyo verde, Una vez, Maleza, and Sin palabras remain staples of contemporary tandas. The early years of their collaboration yielded many lasting gems, including once-ubiquitous titles like Príncipe and Dos ojos tristes, which have largely fallen out of rotation.

Yet the 1949–50 sessions that followed—more somber, more melodramatic, with subtle departures in melody, pacing, and orchestration—have been overlooked. These tracks occupy a middle ground between the rhythmic clarity of the earlier period and the theatricality that gathered momentum from 1951 to 1954, in tangos like Barro, Desvelo, La última copa, and Pasional. The shift is first evident in the gorgeous 1948 recording of Déjame en paz, which foreshadows the sound of this transitional period. Distinct in mood and form, these recordings have rarely circulated in playable condition. Many milongueros will know only the 1950 recording of Cobardía, which has long been paired with Cafetín in tandas of Morán.

Jin’s restorations might change that. Volume Two of TangoSparks offers the most coherent transfers of these tangos to date. Cobardía and Frente a una copa recover their vocal shape and dynamic range. Descorazonado, Cadenas, and Llámame breathe again; earlier versions felt collapsed, with violins dulled and bandoneón passages muffled and inert. Llevátelo todo and Y volvemos a querernos finally land on pitch. For those composing tandas beyond familiar terrain, these fresh releases are valuable additions to the repertoire.

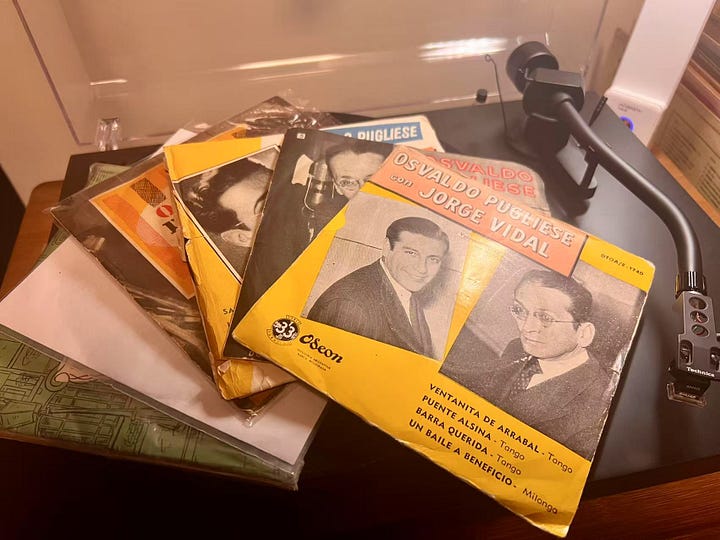

Jorge Vidal, who recorded with Pugliese in 1949 and 1950, has received little more recognition than Morán’s transitional work. Recruited by Pugliese’s musicians at his regular set in Café Argentino on the Avenida Corrientes, Vidal joined the orchestra abruptly and recorded a mere eight songs marked by rhythmic poise and a resonant baritone.25 His tenure was brief, and his name now surfaces mainly in sets curated by seasoned DJs for sophisticated crowds, or in the late-night hours of marathons when deeper wells are drawn from to stir bleary dancers, or to bring them over the top. Nevertheless, Osvaldo Natucci’s La Fiesta del Cuarenta devotes a tanda to Vidal, in volume 37—a testament to the quality of these pieces.26

In my view, whatever neglect Vidal’s output suffered over the past thirty years owes less to the material than to the medium. For decades, off-pitch, poorly balanced, and muddled transfers hid the beauty of these recordings. Volume Three of TangoSparks restores them to proper focus.

The singer’s delivery was firm and centered, emotionally charged yet tautly controlled. Unlike Alberto Echagüe, Alberto Podestá, Roberto Rufino, and Jorge Maciel—who embraced operatic flourish in the late 1940s and early ’50s—Vidal resisted ornament. His phrasing, angular and unhurried, carried the tonal gravity of Edmundo Rivero, Jorge Durán, Jorge Casal, and Oscar Larroca. He had neither the sober reserve of Ángel Vargas, nor the agile register of Floreal Ruiz and Armando Laborde, nor the glossy sheen of Raul Berón and Oscar Serpa. Instead, his style met Pugliese’s ensemble on its own terms: deliberate, forceful, and—borrowing Ruggiero’s word—preponderant. In this respect, Vidal, filled a niche long left vacant by Chanel and Morán.

Puente Alsina, La cieguita, Barra querida, Vieja recova, and Ventanita de arrabal now emerge as viable additions to the social and competition floor—coherent, direct, grounded. Pitch is noticeably superior to official CD releases, especially in the crucial phrases and cadenzas for violin that counterbalance Vidal’s masculine sound. For those willing to look beyond Chanel and Morán—or for performers and competitors seeking fresh interpretive terrain—these tracks open new possibilities.

What sets Jin’s work apart is not a sweeping reinterpretation of Pugliese’s music, but a methodical approach grounded in hands-on experience with analogue restoration and a few well-honed technical innovations. Compared to earlier-circulating versions, these transfers offer steadier pitch, more coherent equalization, and greater clarity. For the first time since their original release, some tracks are now viable for both social dancing and exhibition.

3. An Interview with Frank Jin

To understand his process more fully, I spoke with Jin directly about the choices that shaped TangoSparks’ first release, plus his opinions on musicalization.

Hashimoto: What is your philosophy as a tango restorationist? What is your technology stack for restoring tracks? Why is equalization methodology and the de-emphasis curve so important to your work? How does your musical training figure into your work?

Jin: My philosophy is simple: to recreate the original sound of each tango recording as faithfully as possible. That starts with acquiring every available source—78 RPM shellacs, early LPs, and EPs—in the best condition I can find. Once I have the material, I clean and catalog each item, run test transfers, and select the best source. Pitch confirmation is part of that process.

In terms of de-emphasis curves, I usually select curves based on the year and my own experience. After working with enough recordings, you begin to recognize the correct curve almost instinctively. But that’s only possible with equipment that gives you those options. We typically use a laser turntable, which replaces needle selection with laser-angle adjustment, and which in general offers very flat frequency responses.

Signal extraction from the left and right groove walls is another critical step. With 78s, it’s usually straightforward, but many early vinyl records have asymmetries between the left and right channels due to how they were mastered. In those cases, I use a method I call portionized mixing: blending the signals from each channel in different ratios. This is handled in the analogue domain with specially designed equipment.

Post-production goes well beyond basic de-clicking, de-humming, or de-thumping. Subtle equalization work is often necessary. Essentially, this means reverse-engineering the frequency imbalances introduced by historical limitations such as microphone placement, lathe cutting, and mastering errors common in this early era. In the 78 era, microphone placement shaped nearly everything. By the LP era, certain tonal adjustments became possible through fixed-frequency equalization, so more equalization “carving” is sometimes needed.

Occasionally, I combine segments from multiple takes when doing so improves the overall quality of the result. My musical background helps me identify the correct instrumental timbres, which informs both curve selection and EQ.

I have absolute pitch, although after long sessions, it becomes unreliable. So, I always keep a keyboard nearby, which is more trustworthy.

Hashimoto: This first project of yours focuses on the 1949–50 period and the work of Osvaldo Pugliese. Who is this for? Why this orchestra? Why these years? Musically, setting aside restoration issues, what distinguishes this two-year period from his earlier work?

Jin: I’d say my main audience is tango DJs and collectors. Those are the people who care deeply about both sound quality and musical details. Of course, dancers and music lovers are welcome to enjoy the music too, and we do publish our releases on Spotify. These are compressed versions (at near CD quality) subject to the platform requirements.

Musically, by the mid-1940s, Pugliese had already begun to shed the influence of Julio De Caro and develop his own intensely expressive style. By 1949–50, that style had reached a high-point, although it remained quite close to the spirit of his earlier ‘40s work.

The real reason I began with this period, though, is the audio quality. These two years marked a transitional phase for Odeón in terms of recording technology. And frankly, no available transfer I’ve heard from this period meets the standard. I wanted to offer the best version of this music that’s ever been heard.

Hashimoto: Why do careful listeners hear such marked differences in the sound quality of different restorationist releases? Which releases do you consider the best, and why?

Jin: Many factors matter: the quality of the source, the transfer equipment, and the post-production choices all matter. Some restoration engineers I admire include Mark Obert-Thorn and Andrew Rose [of Pristine Classical]. Their work, mostly in the classical domain, can transform damaged or obscure recordings into something that feels almost new. Peter Copeland’s Manual of Analogue Sound Restoration Techniques is essential reading. I also learned a great deal from Andrew Hallifax, a sound engineer who worked at TangoTunes.

Hashimoto: In cases where discs are scarce or degraded, do you ever consider working from the most authoritative CD transfers, particularly those issued by rights-holding labels, which may have had access to masters in unusually pristine condition before wear or time took their toll? Is there ever real value in correcting those transfers through forensic restoration, or is it always preferable to return to the best available analogue source, even if that requires a longer hunt?

Jin: We do not restore from CDs, primarily because the CD format, while adequate for casual listening and DJ use in many settings, does not meet the standard required for professional editing and high-quality reissue work. If a CD has already been well mastered and sounds excellent, there is often little justification for the effort of locating and transferring another source. Our focus is better spent on recordings that genuinely deserve and can benefit from superior restoration.

That said, in my personal work, I do sometimes tweak CD transfers to improve their sound, mainly by correcting minor pitch issues and making subtle equalization adjustments. For most post-1955 recordings, I’ve found this to be the most practical and effective approach.

Hashimoto: When do you play Pugliese at a regular milonga, and how do you build those tandas? What about festivals and marathons?

Jin: I usually play ‘40s Pugliese early in the evening, especially when I want to raise the energy quickly. His '‘50s work tends to appear later in the night, often during the peak. At festivals and marathons, I give more space to the late Pugliese, and to Morán.

I build tandas onsite. To do this well, you need to understand changes in orchestra lineups, their historical evolution, and even the technological context of the recordings. Over time, you naturally begin grouping tracks by period, and that becomes reflected in your tanda construction.

You usually don’t mix recordings from different periods, unless there are very specific reasons.

You can usually tell a DJ’s level and taste by their tandas. I recommend the Discology section on the TangoSparks website, which we made to help DJs organize their music and build better tandas.

Hashimoto: For DJs working with mixed-quality archives or legacy transfers, what’s your practical advice? How do you decide when a track is “good enough” to play?

Jin: My rule is to use transfers with similar audio quality within a tanda. That consistency matters. Otherwise, dancers and listeners may feel “pulled out of mood” by sudden changes in fidelity.

This is also why most DJs avoid mixing tracks from the 1930s and ’40s with those from the 1950s. The period from 1949 to the early ’50s is especially weird. Every track of that era needs case-by-case basis evaluation. As for stereo recordings that began to surface in the 1960s, DJs should be aware of them and know how to sum them to mono before playback.

To be playable, a transfer should have a strong frequency response across bass, mids, and treble. At minimum, I believe it should be lossless—CD quality or better. But if I have compelling reasons, I would still play a lower-quality track.

4. Reflections

Jin brings together an unusual combination of traits for a tango restorationist: technical fluency in analog transfer, musical intelligence shaped by performance, and a dancer’s sensitivity to phrasing and texture. His background is not incidental. Having danced extensively in Buenos Aires, Seoul, New York, and Beijing—four of the twelve contemporary capitals of Argentine tango27—he understands how phrasing, rhythm, and texture shape not only a room’s mood but also the intangible dynamics of connection, embrace, rhythm, and more. His restorations feel tuned not just for clarity but for actual use, whether on social floors, in exhibitions, or competition rounds.

One of his most distinctive techniques is what he calls portionized mixing, a method tailored to the artifacts of early microgroove vinyl. Though mono LPs should in principle carry identical signals in both groove walls, many transitional-era pressings deviate from this ideal due to inconsistent mastering chains, intermediate transfers on tape or acetate, and variations in cutting stylus geometry. These asymmetries often yield slight channel-phase drift or frequency imbalances, which, when blindly summed, can flatten timbre, blur articulation, or misplace the acoustic center. Jin’s method blends the two groove walls asymmetrically to restore definition and tonal coherence before digitization. The approach appears to rest crucially on his fine pitch discrimination, contextual knowledge, and careful comparative listening.

His broader workflow reflects a similar commitment to judgment-based fidelity. Decisions about equalization, pitch, summing, and de-emphasis are not determined by fixed archival protocols but emerge through iterative listening, guided by historically grounded musical expectations.

Since the end of tango’s Golden Age, Argentina has seen weak intellectual property enforcement and minimal public funding for musical preservation. Jin’s decision to release restorations directly to streaming platforms is unusual among leading restorationists but appears calibrated to this environment. Royalties provide one incentive. More importantly, the move acknowledges how many listeners (and new DJs) now discover tango through Spotify, YouTube, or Apple Music, often unaware they are hearing inferior, pirated copies. In this context, releasing high-quality restorations through official channels serves a dual purpose: asserting authorship and setting recognizable standards of quality. If unauthorized copying is unavoidable—and most restorationists concede that it is—it is better that listeners encounter the good stuff and learn to appreciate it. This approach does not supplant the role of full-resolution files, which serious DJs and audiophiles still pursue for advanced playback. But it broadens access while differentiating credible restorations from the distinctly subpar transfers that presently saturate the internet.

In this light, Jin’s strategy is not a wholesale embrace of open distribution, but a pragmatic assertion of control in a landscape defined by convenience and weak enforcement. It would not be surprising if others eventually follow. TangoTunes and Tango Time Travel, for now, maintain tighter control via download-only portals, rewarding DJs who invest in premium audio chains. But as piracy persists, even these flagships may be drawn into the open, eventually publishing their extensive catalogues to the dominant streaming platforms.

5. Coda

Listeners across the United States, Europe, and China are already starting to hear these restorations, with Spotify accelerating their reach. Jin hasn’t outlined a public plan, but his recent output offers clues. His latest releases focus on Pugliese’s 1951–52 sessions, including improved versions of Entrador and Olivero and multiple studio sessions for La Tupungatina, Pasional, La noche que me esperes, and Barro.28 If this pattern holds, Jin may continue concentrating on the transitional microgroove period—roughly spanning 1948 to 1953—when production shifted from shellac to vinyl and tape, but many releases still bore the imprint of earlier workflows.

That would be welcome work. Much of the Golden Age catalog remains in compromised condition. Between 1948 and 1952, the orchestras of Troilo, Di Sarli, D’Arienzo, Caló, De Angelis, Biagi, Gobbi, Varela, Sassone, and D’Agostino’s alumni—especially Eduardo Del Piano and Armando Lacava—were packed with generational talent and produced hundreds of tangos ideally suited to the social floor. For those seeking more complexity, recordings from Horacio Salgán, Astor Piazzolla, and the duo of Enrique Francini and Armando Pontier offer rich possibilities. Yet many of these tracks survive only in flawed transfers—mis-pitched, muddled, and poorly equalized.

This is the central paradox of the microgroove transition years: just as arrangements and musicianship were reaching new heights, the production chain began to falter. Troilo’s sessions with Discos T.K., Biagi’s tangos with Hugo Duval, De Angelis’s early work with Larroca, and instrumental highlights from Varela, Sassone, and Francini-Pontier all exemplify the problem.29 These are not obscurities; they are core contributions to the genre during a brief but consequential moment of innovation—shaped by a postwar boom in creativity, as wartime ensembles restructured, as virtuosi like Piazzolla, Troilo, and Gobbi stretched the genre, and as tango adapted to export markets and LP-format listening.

That very shift, however, brought new complications. Many recordings from these years are more complex, less rhythmically direct, and harder to interpret than the tightly phrased tangos of 1939–41 that still anchor most milongas. Some works from this period are unlikely ever to suit a crowded floor—but they are ideal for exhibitions, choreographies, and advanced pista rounds in competition. Others align closely with the evolving musical aesthetics of the late ‘40s and deserve far more play than they receive. What holds them back is not their form, but their fidelity. While a few early tape-era recordings survive in acceptable condition, many from the microgroove years remain in bad shape. Their musical depth remains largely untapped—not due to artistic limitations, but because the available versions don’t meet the practical needs of DJs, dancers, and choreographers today.

Consider Sassone’s El relámpago, Maderna’s Ahí va el dulce and Escalas en azul, De Angelis’s Entra nomás and Pasional, or Que se vayan and El motivo as sung by Vargas—sublime performances that still languish in degraded condition. Even Biagi’s Racing Club, A la gran muñeca, and El recodo are a bit of a mess. Or take Caló’s Tú, Los mareados, La última cita, and Mi moro—all still confined to poor transfers.

The arrangements of Francini and Pontier from 1949 to 1953 remain strikingly underplayed, despite their potential to reshape both the social floor and the stage.30 Works like A los amigos, Para lucirse, A pedido, Pecado, Blue Tango, and the enigmatic Discepolín and Una triste verdad sung by Héctor Montes are seldom heard—in large part, because the only available digital editions fall short of modern standards of fidelity. This same period includes seven tangos recorded with Podestá, among them the exquisite Tu piel de jazmín, Che bandoneón, and Una historia como tantas. It also spans the full arc of Julio Sosa’s distinctive tenure with the orchestra—fifteen tangos in total, including the remarkable vals El hijo triste, a duet with Podestá, and the tango Tenemos que abrirnos. Admittedly, Sosa’s recordings are a hard sell for many social floors, except those already attuned to the richer stylizations of singers like Echagüe and Vargas. But such floors do exist, particularly in parts of Latin America. More importantly, choreographers and performers are always looking for material with emotional breadth and structural richness. This repertoire offers both.

The range of what is achievable is broader than many have thought. The old canard—that this music is simply too old to improve—no longer holds. Jin’s work makes that clear. Nor is he alone. Projects elsewhere have shown that careful, informed restoration can recover more detail, balance, and energy than once seemed possible.

Jin’s growing command of this transitional repertoire positions him to make a lasting contribution. Still, later phases of the Golden Age pose different technical and archival challenges that may shift his focus. What comes next will depend as much on access as on intent. Collections of discs remain locked in private collections across Asia and the Southern Cone, some only now beginning to open. They will quietly shape the next frontier. But in my view, the early vinyl era—and the chaotic, often improvised shift to microgroove—remains among the most fertile ground.

Acknowledgements: I an unaffiliated with TangoSparks and have no financial interest in the project; this essay constitutes my independent writing. I am grateful to Frank Jin for his generosity in sharing both his time and insights into the technical and musical dimensions of his restoration work, as well as for providing original photographs from the TangoSparks Studio in Beijing. I am also grateful to Jens-Ingo Brodesser and Howoon Chung for their feedback on early drafts, and to the staff of the Doe Library at the University of California, Berkeley. The views expressed and any remaining errors are my own.

© 2025 Barry Hashimoto. All rights reserved. No text of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior written permission from the author, except brief excerpts for review or scholarly citation.

In addition to the so-called Big Four orchestras of the Golden Age—Carlos Di Sarli, Aníbal Troilo, Osvaldo Pugliese, and Juan D’Arienzo—at least fourteen others contributed substantially to the recorded canon of the Golden Age and its margins, particularly the repertoire most favored by dancers and DJs over the past century. Among the most central are Miguel Caló, Ángel D’Agostino (and his orchestra’s alumni), Pedro Laurenz, Ricardo Tanturi, Rodolfo Biagi, Alfredo De Angelis, Lucio Demare, Héctor Varela, Enrique Rodríguez, Osvaldo Fresedo, Edgardo Donato, Francisco Canaro, Francisco Lomuto, and the studio collective Orquesta Típica Victor. A third echelon might include another twenty or so figures, though by that point the list becomes increasingly marginal.

Recent releases for these key orchestras have been published by TangoTunes and Tango Time Travel.

According to Jin’s research, Pugliese’s recordings at Odeón transitioned to microgroove mastering in May 1949, beginning with the session for Chuzas and Frente a una copa, and concluded in June 1952 with La Tupungatina and Ahora no me conocés.

To be fair, Malandraca (1949) and De floreo (1950) come about as close to universal acclaim as anything in Pugliese’s oeuvre, favored as much or more as recordings as beloved as Recuerdo (1943), Tierra querida (1944), Dandy (1945), Flor de tango (1945), Una vez (1946), La yumba (1946 and 1952), Patético (1948), Chiqué (1952), La tupungatina (1952), Emancipación (1955), Nochero Soy (1956), Pata ancha (1957), Gallo ciego (1959), Don Agustín Bardi (1961), La mariposa (1966), A Evaristo Carriego (1969), and Zum (1973). Indeed, my sense is that few tangos in the genre have been as widely performed as Malandraca (see footnote 19).

Perón’s Justicialismo courted workers while criminalizing their Marxist vanguard. From 1946 on, “vertical” unions were re-chartered under state-supervised elections that excluded Communist slates; dissident locals were decertified, leaders surveilled, and the 1946 Law for the Defence of Democracy empowered preventive detention. Parallel controls swept culture: lyric boards vetted songs for patriotic criteria, radio quotas reserved prime airtime for regime-approved orchestras, and royalty advances flowed almost exclusively to artists who echoed official themes. Artists like Pugliese therefore operated under constant risk of set cancellations, broadcast bans, arrest, and imprisonment. The 1949 constitutional overhaul eliminated presidential term limits, enabling Perón’s 1951 run, and cemented his party’s subjugation of Congress and the judiary, collapsing the separation of powers. For the politics of this period, see Steven Levitsky, Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America: Argentine Peronism in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003); and Daniel James, Resistance and Integration: Peronism and the Argentine Working Class, 1946–1976 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

My translation from the Spanish of Néstor Pinsón’s April 1992 interview with Morán in Buenos Aires, first published in Todo Tango, follows:

“Look, during my years with Pugliese, though many won’t believe it, I suffered quite a bit. I enjoyed performing for the public, yes, but afterward, in the tango world, there was always envy. The only bandleader who genuinely took pleasure in a singer’s success was Aníbal Troilo—I’m sure of it. The others wanted their singer to score a goal, but when he did, oh, how it pained them—including Pugliese. Never a word of encouragement—just a very sad atmosphere. Your own bandmates would throw you under the bus. The musicians never accepted a singer’s success. I managed to soften my bandleader with affection and loyalty, but when I was about to leave, I told him: ‘This is a rotten apple, boss—it’s full of worms.’ […] And then there was that whole cooperative thing. I even got a higher cut than Pugliese at one point, but it was just dividing up the misery. Now he’s rich, and the rest of us, including his yes-men, we all ended up broke. Though I admit, a few columns at the Palermo racetrack were paid for with my money. He could also be cruel—when my voice wasn’t in good shape, he’d make me sing, for example, El Abrojito, which is very demanding, and he’d pound the piano even harder. Until one day I told him: ‘When I’m not well, don’t ever make me sing that again.’ He said nothing.”

Morán’s take on compensation is not undisputed. According to my translation of an undated interview with Balcarce conducted by Alberto Rasore and José Pedro Aresi, the violinist stated, ‘“Working with [Pugliese] was very profitable. Income was distributed according to an internal valuation system that ranged from 7 to 11 points, with each member assigned a score based on their contribution. Working with Osvaldo was not the same as in other orchestras. We earned more.”

Nor was Morán’s opinion of Pugliese’s character universally shared by the orchestra’s main members. In a June 1998 interview with Herrero conducted by Hernán Volpe, Herrero said: “I spent nearly 25 years with the maestro, which really isn’t a small thing. Life with Osvaldo and the whole orchestra was full of ups and downs. Many of them were true and great friends, as well as colleagues. We endured all kinds of upheavals, but also earned rewards for so much struggle. Let me highlight Pugliese’s unwavering conviction—as a creative and innovative musician, and as a person. At his side, I learned a great deal about music, about tango, and about life. I had the honor of his friendship, in addition to serving for eleven years as the orchestra’s principal violinist.“

For members of Pugliese’s orchestras, see the rosters compiled by Oscar Del Priore. Biographical sketches of Carrasco and Camerano (by Volpe), Balcarce (by Alberto Heredia), and Herrero (by Abel Palermo) all appear in the online encyclopedia, Todo Tango. Heredia identifies Herrero as first violin, though other sources assign that role to Camerano. Palermo, for example, identifies Camerano as first violin until 1958, after which Herrero is said to have taken the position. Volpe’s 1998 interview with Herrero, partially presented in footnote 5 above, does not quite resolve the discrepancy.

Balcarce’s creative role in the orchestra, which began in 1949, marked the start of a career that would later span two landmark ensembles: first, as a core member of the Sexteto Tango—alongside Ruggiero, Herrero, Rossi, Víctor Lavallén, Julián Plaza, and Jorge Maciel—and, in 2000, as a founding figure in the Orquesta Escuela de Tango.

The original rights to Argentine Odeón masters remain with EMI-Odeón, the Buenos Aires-based affiliate of the global Odeón label. These rights were preserved through successive corporate reorganizations: first under EMI, and later under Universal Music Group following its acquisition of EMI in 2012. Official reissues from this catalogue have been published primarily under EMI’s own imprint or curated series such as Reliquias and Archivo Odeón, with direct access to master discs or tapes. In contrast, independent reissue labels—including El Bandoneón (Spain, est. 1988), Magenta (Argentina), Lantower (Argentina), others under the Blue Moon group, and a list of other purveyors—operated without formal licenses, relying instead on public domain and fair use exemptions, particularly in Europe. These editions typically drew from commercial 78 rpm pressings and often compiled recordings from multiple original labels. Transfer quality varied widely.

The typical three-step matrix used to press a single 78 rpm side consisted of a father, mother, and stamper (components made primarily of nickel, with traces of copper, silver, and other metals) together weighing approximately 500 grams. For a detailed source on matrix electroforming and shellac pressing from a former senior lecturer at the BBC’s Technical Operations section, see Percival J. Guy, Disc Recording and Reproduction (London: Focal Press, 1964).

For TangoTunes editions, sourced from various 78s and LPs, see the catalog entries available on their website here.

Ruggiero, the composer of N.N., never assigned the piece a formal title; when the orchestra recorded it in 1947, they simply retained the placeholder initials. These did not stand for a name but for the absence of one: nomen nescio, the Latin legal phrase meaning “I do not know the name,” long used in Argentine police and judicial records to identify unnamed or unidentified persons. In everyday Spanish, it is commonly glossed as ningún nombre or no nombre. The title thus underscores the anonymity of the work’s origins. Additional background is available in Michael Lavocah, Tango Masters: Osvaldo Pugliese (Norwich: Milonga Press, 2016). While the 1947 recording has remained the most widely heard version, the orchestra recorded a second take in 1952, seldom circulated due to limited digital availability but now accessible through the recent digitization of the LDS 103 vinyl by Tango Time Travel. In 1968, several veterans of Pugliese’s ensemble—including Ruggiero, Herrero, and Rossi, all present in the original session—formed Sexteto Tango and recorded an avant garde arrangement of N.N., first issued on Presentación del Sexteto Tango and later re-released on the 1994 compact disc Sexteto Tango de FM Tango Para Usted by BMG Argentina.

Carrasco’s trilogy of greatest compositions consisted of Flor de tango, De floreo, and Mi lamento, each composed in collaboration with Ruggiero, according to Volpe’s biographical sketch of Carrasco.

While sources disagree on whether Camerano or Herrero served as first violin in 1949–50, Volpe attributes the lead role from 1939-58 and De floreo specifically to Camerano.

The Reliquias CD and EMI Odeón CD containing De floreo are catalogued in Bernhard Gehberger’s database. Each features a distinct transfer or remastering of the track.

While no studio log survives to identify the piano used during Osvaldo Pugliese’s recording sessions in the 1940s, it is reasonable to infer that a Steinway, Bechstein, or Bösendorfer was used. These brands have long been the standard in Buenos Aires recording studios and concert halls.

The 1949 recording of Malandraca by Osvaldo Pugliese’s orchestra has become a proving ground, an exhibition piece with unusual staying power. To choreograph or improvise to it is, in effect, to crystallize and exhibit the distinctive qualities of a partnership. Among those with filmed performances are Milena Plebs and Pablo Pugliese; Claudia Codega and Esteban Moreno; Ezequiel Paludi and Sabrina Masso; Ariadna Naveira and Fernando Sánchez; Federico Naveira and Inés Muzzopappa; Jonathan Saavedra and Clarisa Aragón; José Luis Salvo and Carla Rossi; Manuela Rossi and Juan Malizia Gatti; and Fausto Carpino and Stéphanie Fesneau. José Luis Ferraro has danced the piece twice—first with Rika Fukuda, later with Paola Tacchetti. Octavio Fernández has returned to it three times, performing with Gladys Barreiro, Soledad Larretapia, and Corina Herrera.

Other notable interpretations include those by Delfina Pissani and Diego Martín Valero; Virginia Vasconi and Jaimes Friedgen; Mariela Sametband and Guillermo Barrionuevo; Paula Tejeda and Lucas Carrizo; Cecilia Piccinni and Ricardo Biggeri; Cecilia González and Donato Juárez; Silvana Anfonsi and Rodrigo Fonti; Vicky Pesci and Lucas Martin; Selçuk Atalay and Müge Üner; Lina Chan and Bülent Karabagli; Vaggelis Hatzopoulos and Marianna Koutandou; Sabrina Tonelli and Vladimir Khorev; MiSun Kang and Ariel Taritolay; Naomi Hotta and Leo Ortiz; Esref Tekinalp and Vanessa Gauch; Jennifer Bratt and Ney Melo; Sara Grdan and Iván Terrazas; Eva Guerrero and Bastien Bollon Duret; Giselle Galicia and Roque Castellano; Natalia Fures and Gerónimo Dorkas; Diana Cruz and Nick Jones; Laura Grandi and Facundo Gallo; and Maria Vaitso and Giannis Lado. Even this extensive list is almost certainly incomplete.

Although Pugliese’s 1949 version remains the most widely favored, alternative arrangements—most notably by Roberto Álvarez’s Color Tango, first released on the 1998 album Con Estilo Para Bailar, Vol. 1 by Sello Típica Records—have also drawn the attention of professionals. Among them are Milena Plebs and Ezequiel Farfaro; Claudio Gonzalez and Melina Brufman; Lorena Ermocida and Pancho Martínez Pey; Horacio Godoy and Karina Colmeiro; Emilie and Pablo Tegli; and Isabel Costa and Nelson Pinto. A 2005 live performance by Color Tango in Buenos Aires featured Corina de la Rosa and Julio Balmaceda [video]; another, in Chicago in 2007, paired Michelle Lamb with Murat Erdemsel [video]. One of the most memorable stagings of this version was a November 1999 ensemble tribute to Nito and Elba García, featuring the dancers Geraldine Rojas, Javier Rodriguez, Natalia Hills, Oscar Mandaragan, Mariana Montes, and Sebastian Arce [video].

The TangoTunes edition of Malandraca based on shellac matrix 17307-30604 is available here. The company has not yet issued a release of the song based on a vinyl source.

Interviewed in 1992 by Eduarda Rafael for La Maga, Ruggiero stated “My tangos were born and died in the Pugliese’s orchestra, for example Catuzo, N.N., A mis compañeros, Yunta de oro. . . Osvaldo was the best follower of Julio De Caro, but he went his own way after La yumba and Negracha. With those tangos the real Pugliese was born, remaining faithful to the rhythmic preponderance that comes from the beginnings of tango.” An excerpted transcript is here.

Alternatively, the Catuzo heard in video of Saavedra and Aragón’s exhibition may derive from an earlier TangoTunes transfer sourced from shellac matrix 17516-30608. That edition is available here.

For the TangoTunes release of Catuzo based on the 1972 LP Historiando a Osvaldo Pugliese, Vol. 1, see here.

By 2025, twelve cities stand out as the capitals of Argentine tango: Buenos Aires, followed (somewhat debatably but with reason—and in no particular order) by Seoul, San Francisco, Moscow, New York City, Berlin, Tokyo, Beijing, Paris, Los Angeles, Istanbul, and Medellín. Each brings its own take on the tradition, shaped by history, migration, and local culture. A handful of other global cities have vibrant communities, pockets of deep talent, and rich local histories, but don’t quite match the depth, continuity, and sheer density of the front-runners. Still, Montevideo, Santiago, Kyiv, Rome, London, Athens, and Montreal merit honorable mentions.