Translation #2: Pugliese-Chanel 1943-1945

Ten tangos from the early Chanel period

This essay examines the early years of Roberto Chanel’s collaborations with Osvaldo Pugliese, focusing on the lyrical tangos recorded by this duo between 1943 and 1945. These timeless works, beloved by Argentine professionals and still played weekly around the globe, showcase the enduring power of tango as both art and cultural memory. The essay introduces ten fresh translations, including an original rendering of the cryptically raucous Corrientes y Esmeralda packed with vice, violence, and urban code. A detailed analysis of the themes, symbols, and historical context uniting these tangos is presented. A companion essay, Translation #1: Pugliese-Chanel 1945-1947, covers ten tangos from the final years of their partnership and is available elsewhere on this blog.

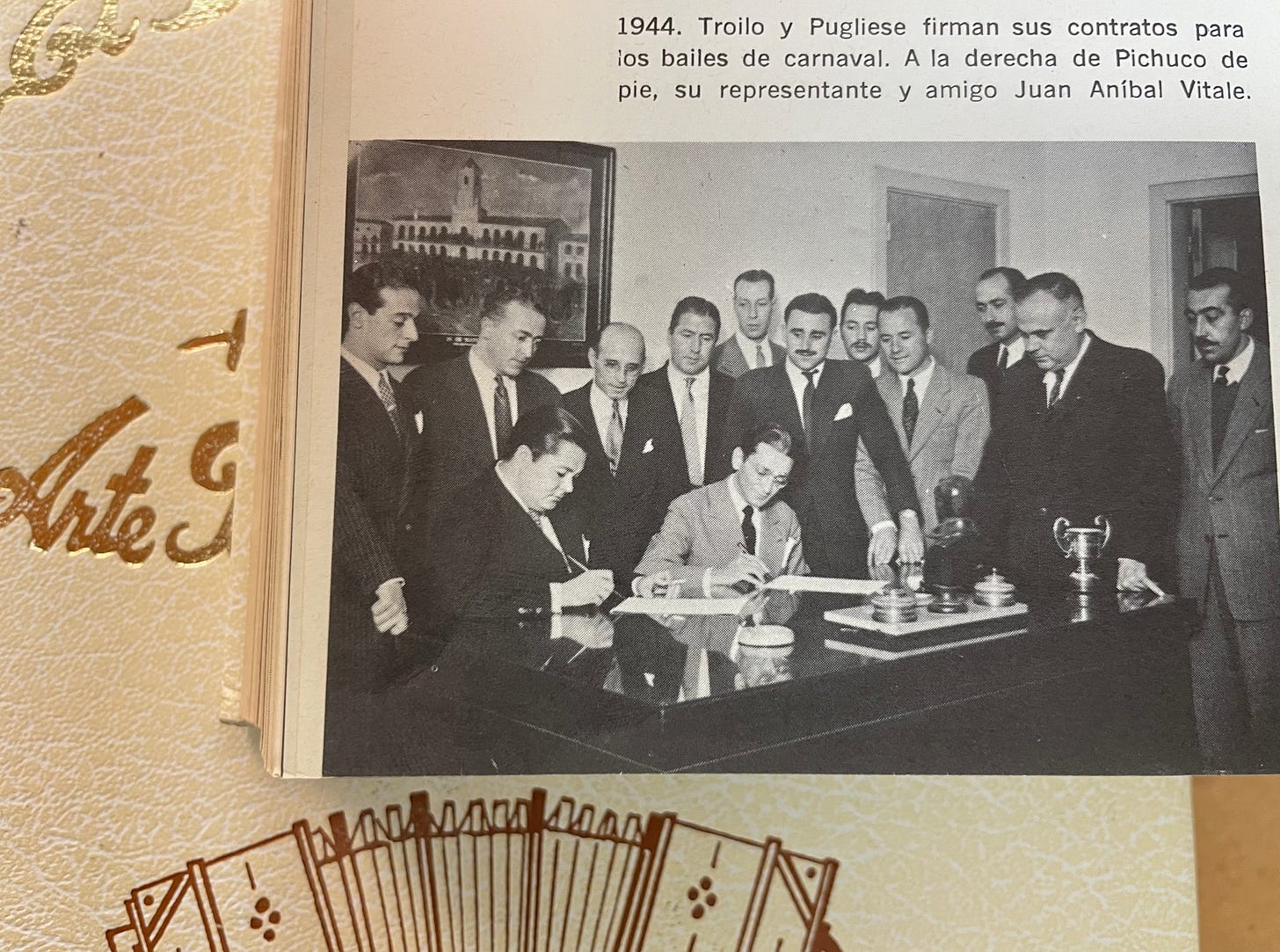

Photos: Ferrer, Horacio. El Libro del Tango: Arte Popular de Buenos Aires. Edited by Antonio Terson. 3 vols. Buenos Aires: Patrón, 1980.

Introduction

On a humid night in 1943, a crowd of porteños packed into a dance hall somewhere in central Buenos Aires. Men in broad-brimmed hats and women in their finest dresses moved to the rhythms of a nation undergoing serious change. The orchestra leader, Pugliese, and his new singer, Chanel, delivered a repertoire of tango recently etched in metal at Estudios Odeon, music we now know has withstood the test of time. In a country where tango had risen from the slums to become a national art, their work captured the tension between aspiration and alienation, ambition and despair. Argentina, at a crossroads between oligarchic, authoritarian rule and the aspirations of its working class, found its struggles mirrored in the lyrics and melodies of this duo, and the brilliant musicians backing them.

This essay revisits the early years of that collaboration, from 1943 to 1945, when Pugliese and Chanel composed works like Corrientes y Esmeralda, Galleguita, Muchachos comienza la ronda, Silbar de boyero, Farol, Qué bien te queda (Cómo has cambiado), Rondando tu esquina, La abandoné y no sabía, Nada más que un corazón, and El tango es una historia. These tangos, forged in upheaval, were characteristically sentimental, and while they did not shy away from sensitive topics, they put them in coded language. Employing Quentin Skinner’s contextualism and Leo Strauss’s esoteric reading, I explore how these poems not only engaged with the immediate struggles of prewar Buenos Aires but also embedded subversive critiques of nationalism, class dynamics, and industrial displacement. Ultimately, Pugliese and Chanel’s work exemplifies how tango could act as both a mirror of societal fractures and a populist act of defiance against political authority, social structures, and economic forces.

Even today, the cultural power resonating through these poems is evident in performances by elite tangueros dancing with mastery and depth.

Themes and Symbols

The tangos of Osvaldo Pugliese and Roberto Chanel from 1943 to 1945 illuminate themes of treachery, decay, salvation, and resilience, weaving personal anguish with the collective struggles of Buenos Aires. Urban imagery serves as the foundation for many works, such as Corrientes y Esmeralda, which gives a kaleidoscopic view of a chaotic city corner, where political violence collides with cabaret culture, youths are destitute or unruly, and innocence is lost in vice, substance abuse, and grift. This degenerate center of the city is honored in bold tones of reverence. In Pugliese’s recording, Chanel exudes an edgy bravado, while Ruggiero’s bandoñeons, sharp and staccato, hit the air like a dandy’s gloved fist.

Displacement and alienation take center stage in Galleguita, where the tragic arc of a young female immigrant exposes Buenos Aires as a land of broken promises, exploitation, and betrayal. Arriving with nothing but Moorish eyes and a delicate frame, she becomes ensnared in the city’s undercurrents. Her drive to send money back to her mother leads to her moral and physical undoing; her virtue—like a ball of snow—melts away in the streets of Pigalle. Her ruin is hastened by a jealous lover, spurned and vindictive, who poisons her mother’s life with tales of disgrace. The black-edged letter he sends severs familial ties and symbolizes the moral decay of exile. Yet, even in the depths of betrayal and loss, Galleguita clings to a fragile dignity, aggrieved but alive.

In Farol, the cross-shaped streetlamp becomes a symbol of both resilience and decline, blending Christian imagery with Nietzschean irony. It stands as a silent witness to lifetimes of toil and survival in a working-class neighborhood. The streetlamp’s fading light, once vibrant and tied to tango’s vitality, evokes Nietzsche’s vision of endurance in On the Genealogy of Morality, where suffering is transformed into a source of strength against oppression. Resisting the erosion of time, it keeps vigil over the slumbering suburbs, defying the hardships of wind, rain, and fog.

Farol paints a portrait of a working-class neighborhood, its tin houses gleaming with sorrow and its streets steeped in collective memory. The poem’s narrative unfolds at a melancholic early morning hour, when the streetlamp, a silent witness, watches over the corner’s history of toil and resilience. The farol stands as both a literal light source and a symbolic touchstone for the dreams, struggles, and fading vitality of the workers who populate the arrabal. Its dimming light, once vibrant and intertwined with the tango, now mirrors the erosion of collective strength in the face of time and hardship. The wind carries the voices of a million workers and whispers the verses of the poet Evaristo Carriego, grounding the poem in a shared cultural and emotional landscape where poetry and music preserve what labor and struggle have strained to sustain.

Other tangos focus on personal loss and its reverberations. La abandoné y no sabía captures the aching regret of a man who realizes too late that he loved the woman he abandoned. His sorrow echoes in a mournful bandoneón, the dance floor a space where grief and memory dance old sorrows. Rondando tu esquina explores obsessive longing, following a protagonist who circles the streets of his lost love, consumed by a relentless passion that wounds him, defines him. Silbar de boyero shifts to the mythical rural expanse of the Argentine pampas and shepherds, cousins of the idealized gaucho cowboys. The poem exudes tango’s themes of solitude and searching for transcendence of some sort. The herdsman’s whistle, slow and melancholic like the wail of a willow is wordless lament for a love forever out of reach—the pastoral and the romantic blend seamlessly amid an ethereal melody and some unknown bandmember whistling through it all. Nada más que un corazón reflects love’s fragility, as its narrator, stripped of worldly wealth, offers only a humble heart—simple, sentimental, and filled with devotion.

Still other tangos turn inward, reflecting on the evolution and essence of the genre itself. Qué bien te queda critiques tango’s transformation from a raw, working-class expression to a polished urban art form, lamenting the loss of authenticity in its refinement. In contrast, El tango es una historia celebrates tango as a living repository of memory, born humbly but immortalized by the harmonies of bohemian creators. Together, they frame tango as both a lament for its past and a vessel of shared sorrow and identity. Meanwhile, Muchachos comienza la ronda juxtaposes the joy of dance with a subtle critique of hedonism and escapism, suggesting that beneath the revelry lies a persistent unease. These tangos reveal tango as a form that transcends mere personal grief, the hackneyed image it is often recieves.

Across these poems, the city becomes a place of loneliness, betrayal, and survival—but most of all, of endurance. They tell stories of the pure and the weak persevering amid the debased, the strong, the vengeful, the violent. Galleguita and Corrientes y Esmeralda present Buenos Aires as a stage where innocence is lost, and survival demands both strength and compromise. Farol and Nada más que un corazón focus on vulnerability, showing how it can transform into quiet resilience. These poems assert that endurance is not the avoidance of suffering but its sublimation into strength.

In Galleguita, a black-edged letter shatters the protagonist’s innocence, laying bare the brutal realities of urban exploitation and gendered oppression. In Farol, the cross-shaped streetlamp becomes a potent symbol, intertwining Christian sacrifice with Nietzschean defiance, reframing hardship as resistance. Even Silbar de boyero, set on the expansive pampas, carries the city’s burdens through a solitary whistle, suggesting that longing and loss transcend geographical boundaries. Beneath these narratives lies a shared tenacity—the refusal of the weak to be erased by suffering or subjugation.

Tango itself echoes this defiance. Qué bien te queda laments the erosion of the obscure and authentic roots of tango and its replacement with a gentrified reboot, while El tango es una historia celebrates tango as a vessel of collective memory, grief, and resistance. The resilience of tango is mirrored in the recurring totems of all these poems: a whistle, a letter, a ticket, a shadow on the corner.

Photos: Ferrer, 1980.

Interpretations

Between 1943 and 1945, Osvaldo Pugliese and Roberto Chanel recorded a cluster of tangos that illuminate a tapestry of mid-century Argentina. These pieces emerged in the wake of the Infamous Decade’s conclusion with the Revolution of 1943, as the uncanny corporatist authoritarianism that we now know of as Peronism gathered steam. Though Pugliese did not pen the lyrics, his calculated decisions—to select, arrange, rehearse, perform, and ultimately record certain tangos—constituted a potent “speech act” of cultural communication. By using Quentin Skinner’s contextualism with Leo Strauss’s esotericism, we can better understand the layered dialogue in these tangos, which emerges both nationalistic and subversive when seen under this lens.

Tensions of Modernity and Authenticity

Two tangos underscore the tension between artistic refinement and a longed-for authenticity. Qué bien te queda dramatizes tango’s metamorphosis from a raw, nocturnal dance in suburban neighborhoods to a sleek, national emblem admired by a new urban elite. Its speaker hails tango’s newfound prestige—“Skyscrapers, amazed, watch you arrive in a tuxedo”—even as it bemoans the loss of the genre’s rougher, more intimate origins. Such longing resonates particularly in Pugliese’s subtle interpretive flourishes, which animate the piece with a kind of wistful homage to the gritty tenements and streetlamps of his youth. Here, we might invoke Strauss’s argument that cultural products sometimes encode deeper critiques. Beneath the celebratory façade, this tango conveys trepidation about commodification, asking if the ascendance of polished tango inevitably buries its marginalized roots.

From another angle, El tango es una historia, lyrics by Reinaldo Yiso, doubles down on tango as an oral archive of communal memory. The song lifts tango from the realm of mere entertainment to that of cultural chronicle: “Each phrase is a memory, each part a hidden sorrow.” In Pugliese’s hands, this becomes a collective reflection on Argentine identity—a living record of joys, losses, and migrations. Against the backdrop of the 1943 coup, the tango’s insistence on “our story” hints at a bid for unity, albeit complicated by the knowledge that working-class narratives were routinely repurposed to bolster nationalism. In this tension lies a stratified message: the masses might hear a soothing anthem of inclusion, while a minority—particularly those aware of Pugliese’s communist commitments—detect a cautionary note about state cooptation of popular culture.

Critique of Urban Transformations

The cityscapes of Buenos Aires animate several tangos, punctuating the interplay between spectacle and disillusionment. Corrientes y Esmeralda celebrates a bustling corner where guapos (allegedly, street toughs working as political fixers, whipping votes during the Roca regime), quick brawls, and fleeting glamour collide. It revels in a legendary past when “hardmen went silent on your eight corners,” yet also gestures at red-light levels of moral degeneracy and grift. This dissonance between roguish exuberance and harsh economic realities testifies to a culture in flux, grappling with modernization’s promise and peril. Pugliese’s arrangement further accentuates the collision: insistent bandoneóns pulse with both bravado and sorrow, echoing the city’s uncertain pivot toward Peronist populism.

A parallel warning comes from Farol, where Homero Expósito’s lyrics evoke a single streetlamp as a forlorn sentinel of working-class life. Often interpreted by historians as cruciform in older barrios, the streetlamp channels a latent spiritual resonance. Echoing Nietzsche’s insight that the weak transform suffering into strength, Pugliese’s melodic reading turns the dimming light into a brooding emblem of communal endurance. Stripped of overt political slogans, the poem operates as an oblique critique of how swiftly modernization can snuff out older neighborhood solidarities. This unspoken critique—what Strauss might term an “esoteric reading”—ventures that genuine community is eroding under a regime eager to parade tango as national spectacle.

Personal Narratives as Social Commentary

Other tangos deploy intimate tragedy to highlight structural exploitation. Galleguita, for instance, tracks a young immigrant woman who arrives in Buenos Aires “carrying no jewels…but those dark Moorish eyes.” Betrayed by a resentful suitor who reports her “disgrace” to her village, she drifts into the city’s underbelly. The heartbreak is personal, but the subtext is collective: a reminder that immigrants were routinely caught in webs of precarious labor and social marginalization. Pugliese’s hallmark is to balance haunting lyricism with emphatic arrangement, exposing how the illusions of upward mobility often mask deeper forms of injustice.

Meanwhile, Rondando tu esquina amplifies this focus on intimate sorrow as a mirror for collective despair. Its protagonist confesses to an all-consuming passion that devours him, driving him back, night after night, to the same haunting corner. Tango is often pegged as the city’s confessional booth, where the heartbreak of one stands in for the heartbreak of many. Here, that tradition takes on special resonance in the shadow of wartime uncertainties and repressive official policies. The tango registers the sense of a once-forgiving city now turned inward, suspicious, and watchful.

The Subtleties of Collective Festivity

If heartbreak and regret predominate in certain tangos, others invoke the communal embrace of dance and music. Muchachos comienza la ronda—“Boys, the round begins”—encourages the assembly to join the intoxication of nightly dancing, the communal ritual of milongueros. On the surface, this cheerful invitation might appear to endorse nationalist celebrations of tango as an authentic Argentine pastime. Yet by this point in Pugliese’s repertoire, the measure of that “collective round” is shot through with complexity. Behind the spirited vocals lies an awareness that the revival of tango under Perón, though inclusive in some respects, also risked glossing over the class struggles that gave the music its original bite. The tension between open invitation and coded protest marks Pugliese’s approach: a performance that delights wide audiences yet subtly retains its moral sting.

Inner Yearnings and Coded Resistance

A handful of tangos articulate the collision between personal longing and broader cultural malaise in distinctly esoteric ways. Silbar de boyero envisions a solitary herdsman’s whistle as a lament not only of rural isolation but also of urban estrangement. The slow, plaintive melody foreshadows the recognition that Perón’s populist overtures do not heal all rifts. Similarly, Nada más que un corazón enshrines a simple devotion “humble as a song,” opposing genuine emotional bonds to the creeping commodification of relationships. By exalting this modest gift—“all I want is your love”—the tango implicitly resists the era’s drive to monetize cultural forms.

Lastly, La abandoné y no sabía confronts the irretrievability of lost love, aligning an individual’s self-reproach with the city’s fleeting illusions. The protagonist’s regret, shot through with references to dancing violins and heartbreak, resonates with a generational sense that illusions of prosperity or political unity might slip away before being fully grasped. Pugliese’s lento tempo and muted bandoneón transforms this tragedy of the heart into a public lament for Argentina’s political experiment, teetering between liberation and disillusionment.

In Silbar de boyero, Pugliese and poet José Barreiros Bazán invoke the romantic aura of 19th-century gauchesque literature while carefully removing its more incendiary political elements. The solitary figure of the robero echoes the gaucho’s deep bond with the fertile pampas from which sprang the lifeblood of Argentina’s economy and society—the endless plains celebrated in works like José Hernández’s Martín Fierro—but without the defiance, violence, or suspicion such an archetype often provoked. Instead of the volatile, sword-brandishing cowboy, we encounter a humble shepherd whose labor and isolation evoke sympathy rather than alarm. This shift allows the poet to recall the mythos of the iconic gaucho—that proud, open-range drifter—without inciting the political anxieties that had long surrounded Argentina’s legendary cattlemen.

The robero’s identity resonates not only with folk tradition but also with Christian imagery, bridging 19th-century pastoral sentiment and a quiet nod to the Gospels’ shepherd symbolism. In an era marked by the 1943 coup and the subsequent rise of populist power structures, this shepherd figure lends itself to a Marxist reading of class struggle and co-optation: he stands at the margins, alienated from the forces that rule the cities yet still embodying an ethic of care. His whistle suggests both a plea for recognition and a guarded, cryptic resistance to the manipulations of the powerful. Pugliese’s choice of this theme thus merges multiple strands of Argentine cultural memory—gauchesque heroics, Christian humility, and proletarian protest—into a distilled, unthreatening persona that quietly critiques a social order quick to appropriate, but slow to honor, the genuine needs of its workers.

Conclusion

Violence, vice, toil, isolation, moral degeneracy, and vivid song and verse imbue these poems, throwing up a mirror to the face of Argentina in the turbulent years between the regimes of Roca and Perón. The lyrics operate at two levels. On one level, the poems validate Peronist narratives that celebrate tango as Argentina’s unifying cultural property. Yet on another level—more private, more attuned to the thwarted hopes of radical workers—these tangos encode critiques of state-led reform, class betrayal, and cultural appropriation. Much as Skinner would insist on reading texts within their ideological environment, so too must we interpret these tangos as speech acts in the thick of political realignments. And as Srauss suggests, careful attention to the indirect, the ambiguous, and the subtextual reveals a hidden transcript: affectionate tributes to the city that are at once forms of silent defiance. For general audiences, the tangos deliver nostalgic romance, shimmering with aspiration. For the cognoscenti, they preserve a communal memory of injustice—and point quietly toward potential resistance. Their enduring power lies precisely in this dual register. By letting tango speak in two voices—hopeful on the surface, quietly incendiary beneath—Pugliese and Chanel bequeathed a musical legacy that soothes with danceable melodies but also bites hard with critique.

Photo of the poet Caledonio Flores from: Ferrer, 1980.

Photo of the musician Francisco Pracánico from: Bates, Héctor Tomás Octavio, and Luis Jorge Bates. La Historia del Tango: Sus Autores. Tall. Graf. de la Cia, General Fabril, Financiera, 1936.

The Poetry and Translations

The ten tangos of this post brought together an illustrious set of artists, all finding their greatest expression through Chanel’s voice and Pugliese’s piano. Corrientes y Esmeralda (1933) features music by Francisco Pracánico (1898–1971) and lyrics by Celedonio Flores (1896–1947). Galleguita (1925) combines Horacio Pettorossi (1896–1960) as composer and Alfredo Navarrine (1893–1967) as lyricist. Muchachos comienza la ronda (1943) has music by Luis Porcell (dates unknown) and lyrics by Leopoldo Díaz Vélez (1897–1952). Silbar de boyero (1943) was composed by David Barberis (dates unknown) with lyrics by José Barreiros Bazán (dates unknown). Farol (1943) brings together Virgilio Expósito (1924–1997) for the music and Homero Expósito (1918–1987) for the poetry. Qué bien te queda (1944) has music by Vicente Salerno (dates unknown) and lyrics by Juan Mazaroni (dates unknown). Rondando tu esquina (1945) pairs Carlos José Pérez de la Riestra (a.k.a. “Charlo”, 1905–1990) as composer with Enrique Cadícamo (1900–1999) as lyricist. La abandoné y no sabía (1943) was both composed and written by José Canet (1915–1984). Nada más que un corazón (1944) has music by Manuel Sucher (1913–1981) and lyrics by Carlos Bahr (1902–1984). El tango es una historia (1944) combines music by Roberto Chanel (1914–1972) with lyrics by Reinaldo Yiso (1915–1978). Each tango reflects the unique artistry of its creators.

All poems are sourced from TodoTango. For a full discussion of my translation methodology and its guiding principles, see Translating Tango: A New Approach elsewhere on this blog.

Corrientes y Esmeralda • 1933 • Francisco Pracánico • Lyrics by Celedonio Flores

Amainaron guapos junto a tus ochavas cuando un cajetilla los calzó de cross y te dieron lustre las patotas bravas allá por el año… novecientos dos… Esquina porteña, tu rante canguela se hace una melange de caña, gin fitz, pase inglés y monte, bacará y quiniela, curdelas de grappa y locas de pris. El Odeón se manda la Real Academia rebotando en tangos el viejo Pigall, y se juega el resto la doliente anemia que espera el tranvía para su arrabal. De Esmeralda al norte, del lao de Retiro, franchutas papusas caen en la oración a ligarse un viaje, si se pone a tiro, gambeteando el lente que tira el botón. En tu esquina un día, Milonguita, aquella papirusa criolla que Linnig mentó, llevando un atado de ropa plebeya al hombre tragedia tal vez encontró… Te glosa en poemas Carlos de la Púa y el pobre Contursi fue tu amigo fiel… En tu esquina rea, cualquier cacatúa sueña con la pinta de Carlos Gardel. Esquina porteña, este milonguero te ofrece su afecto más hondo y cordial. Cuando con la vida esté cero a cero te prometo el verso más rante y canero para hacer el tango que te haga inmortal. Corrientes and Esmeralda Hardmen went silent on your eight corners when a dandy decked them with a boxer’s cross, and your name got its lustre from rowdy rich kids back in the year nineteen-oh-two. Porteño corner, your noctural ranting is a mix of sugarcane Schnapps and gin fizz, English bets, monte, baccarat, and the numbers, grappa-drunk brawlers and coked-up hustlers. The Odeón puts on airs as the Royal Academy, bouncing tangos off the old Pigall, while a miserable anemic stakes his last bit, waiting for the train back to the slums. From Esmerelda north toward Retiro, French dolls bow their heads in prayer, angling for a john and dodging the cop’s sharp gaze, his stare cutting their heels like a blade. One day on your corner, Milonguita—that Creole muse that Linnig wrote of— dragging her bundle of plebiean clothes, might’ve met her man of tragedy. Carlos de la Púa carved you into verses, and poor Contursi made you his faithful friend. On your hard corner, any squawking nobody styles himself as Carlos Gardel. Porteño corner, this milonguero promises you his roughest, dear devotion. When life’s score reads zero to zero, I’ll give you a verse, raw and rakish, that immortalizes you in tango.

Galleguita • 1925 • Horacio Pettorossi • Lyrics by Alfredo Navarrine

Galleguita la divina… la que a la playa argentina llegó una tarde de abril, sin más prendas ni tesoros que tus negros ojos moros y tu cuerpito gentil. Siendo buena eras honrada, pero no te valió nada que otras cayeron igual. Eras linda, Galleguita, y tras la primera cita fuiste a parar al Pigall. Sola y en tierras extrañas, tu caída fue tan breve que, como bola de nieve, tu virtud se disipó… Tu obsesión era la idea de juntar mucha platita para tu pobre viejita que allá en la aldea quedó. Pero un paisano malvado loco por no haber logrado tus caricias y tu amor, ya perdida la esperanza volvió a tu pueblo el traidor. Y, envenenando la vida de tu viejita querida, le contó tu perdición y así fue que, el mes pasado, te llegó un sobre enlutado que enlutó tu corazón. Y hoy te veo, Galleguita, sentada triste y solita en un rincón del Pigall, y la pena que te mata claramente se retrata en tu palidez mortal. Tu tristeza es infinita… Ya no sos la galleguita que llegó un día de abril, sin más prendas ni tesoros que tus negros ojos moros y tu cuerpito gentil. Little Galician Girl Little Galician girl, so divine— you came to Argentina’s shore one April afternoon, carrying no jewels, no treasures, but those dark Moorish eyes and your delicate frame. Pure of heart, you were honorable, but none of that saved you— others fell just like you. You were lovely, little Galician girl, and after your first meeting, you ended up at Pigalle. Alone in a foreign land, your fall came so quickly, your virtue melting away like a ball of snow. Your obsession was the dream of earning some cash for your poor little mother you’d left in the village. But a cruel scoundrel, crazy with jealousy for the love you denied him, lost all hope and returned to your village, that traitor. There, he poisoned the life of your beloved mother, telling her of your disgrace. And so, last month, an envelope arrived, lined with mourning black, and it drowned your heart in sorrow. Now I see you, little Galician girl, sad and alone, sitting in a corner at Pigalle. The grief that’s killing you is written clear in your deadly pale face. Your sadness knows no end— you’re no longer the little Galician girl who arrived one April day, carrying no jewels, no treasures, but those dark Moorish eyes and your delicate frame.

Muchachos comienza la ronda • 1943 • Luis Porcell • Lyrics by Leopoldo Díaz Vélez

Muchachos, comienza la ronda que el tango invita a formar ¿Quién, al oir el arranque de un son tan brillante, no sale a bailar? Yasí enredar su emoción a esta canción que en nuestras almas se ahonda. Muchachos, comienza la ronda… Vayan pasando al salón. No se pierdan ni un compás de este tango que va cautivando rebelde y dulzón. Entre vueltas y requiebros galantes imaginemos hoy vivir el tiempo de antes; ese tiempo feliz del chambergo bien gris, el piropo locuaz y el farol de arrabal. No se pierdan ni un compás de este tango… Así, al escucharlo, ¡qué lindo es bailar! Oyendo este son tan porteño revive mi corazón… Mientras entono este tango me voy olvidando de todo dolor. Su musiquita cordial y sin igual en nuestras almas se ahonda… Muchachos, comienza la ronda… Vayan pasando al salón. Boys, the Round Begins Boys, the round begins, the tango invites us to form a line. Who, hearing the opening chords of such a brilliant sound, wouldn’t jump to the dance? And so let their emotions entwine with this song that dives deep into our souls. Boys, the round begins… Step into the hall. Don’t miss a beat of this tango, sweet and defiant, that captivates us all. Amid elegant spins and flourishes, let’s imagine today we’re living those times of old— those happy days of grey felt hats, clever quips, and streetlights on the edge of town. Don’t miss a beat of this tango… Oh, how lovely it is to dance! Listening to this porteño tune, my heart comes alive. As I sing this tango, I forget all pain. Its cordial, unmatched music dives deep into our souls. Boys, the round begins… Step into the hall.

Silbar de boyero • 1943 • David Barberis • Lyrics by José Barreiros Bazán

Silbar De Boyero, tristón, como el gemir del sauzal con el viento. Canción sin palabras, dolor, que no logró expresar su emoción. Porque será su silbido, mucho más triste que ayer. Silbar de boyero, que va detrás de un querer. Al cruzar la inmensidad, sólo siente tu ansiedad, sol y huella, pampa y cielo. Pero nunca el corazón que causó tu desconsuelo. Y al sentir el amargor de ese eterno mal de amor que sangrando está en tu pecho. Mientras vas con su recuerdo que te sigue sin cesar, como el buey de paso lerdo, lento y triste tu silbar. Canción sin palabras, dolor… que no logró expresar su emoción. The Herdsman’s Whistle The herdsman’s whistle, melancholy, like the wail of a willow in the wind. A song without words, a sorrow that couldn’t express its pain. Why does his whistle seem sadder than before? The herdsman’s whistle, chasing a love. Crossing the endless expanse, it feels only your longing— sun and trail, plains and sky— but never the heart that caused your grief. And feeling the bitterness of that eternal heartache, bleeding deep in your chest, you carry its memory with you, following you ceaselessly, like the ox’s slow, weary pace, your whistle, slow and sad. A song without words, a sorrow that couldn’t express its pain.

Farol • 1943 • Virgilio Expósito • Lyrics by Homero Expósito

Un arrabal con casas

que reflejan su dolor de lata…

Un arrabal humano

con leyendas que se cantan como tangos…

Y allá un reloj que lejos da

las dos de la mañana…

Un arrabal obrero,

una esquina de recuerdos y un farol…

Farol,

las cosas que ahora se ven…

Farol ya no es lo mismo que ayer…

La sombra,

hoy se escapa a tu mirada,

y me deja más tristona

la mitad de mi cortada.

Tu luz,

con el tango en el bolsillo

fue perdiendo luz y brillo

y es una cruz…

Allí conversa el cielo

con los sueños de un millón de obreros…

Allí murmura el viento

los poemas populares de Carriego,

y cuando allá a lo lejos dan

las dos de la mañana,

el arrabal parece

que se duerme repitiéndole al farol…

Streetlamp

A neighborhood of houses,

their tin walls gleaming with sorrow…

A neighborhood of humanity,

its legends sung like tangos…

And far off, a clock tolls

two in the morning…

A workers’ quarter,

a corner steeped in memories, and a streetlamp…

Streetlamp,

the things you see now…

Streetlamp, not the same as before…

The shadow,

slipping past your gaze today,

leaves my half of the street

even sadder.

Your light,

once pocketed with the tango,

has dimmed and dulled—

it’s a burden to bear.

Here, the sky whispers

with the dreams of a million workers…

Here, the wind murmurs

the folk poems of Carriego.

And when, far away,

the clock strikes two in the morning,

the neighborhood seems to fall asleep,

repeating itself to the streetlamp…Qué bien te queda (Cómo has cambiado) • 1944 • Vicente Salerno • Lyrics by Juan Mazaroni

Hermano, te ha vencido el modernismo, tu figura de ayer también cambió, sólo queda en tus compases melodiosos el pasado corazón a corazón. Ya te alejaste del suburbio que te viera bajo la luz palpitante de un farol, que perfilaba tu figura caprichosa bailando a los acordes, de un organito al son. Qué bien te queda, cómo has cambiado, y en este marco de distinción, vas enredando los corazones entre lamentos de un bandoneón. Los rascacielos llenos de asombro vistiendo smoking, te ven llegar. Qué bien te queda, tango argentino, canción del alma, canto inmortal… How Well It Suits You (How You’ve Changed) Brother, modernity has beaten you, and yesterday’s image of you has changed. Only in your melodious rhythms does the past still speak heart to heart. You’ve left behind the suburb that watched you beneath the pulsing light of a streetlamp, where your jaunty silhouette took shape, dancing to the tunes of a hand organ. How well it suits you, how you’ve changed, wrapped now in this air of refinement, entwining hearts in the laments of a bandoneón. Skyscrapers, amazed, watch you arrive in a tuxedo. How well it suits you, Argentine tango, song of the soul, immortal hymn.

Rondando tu esquina • 1945 • Charlo • Lyrics by Enrique Cadícamo

Esta noche tengo ganas de buscarla, de borrar lo que ha pasado y perdonarla. Ya no me importa el qué dirán ni de las cosas que hablarán… ¡Total la gente siempre habla! Yo no pienso más que en ella a toda hora. Es terrible esta pasión devoradora. Y ella siempre sin saber, sin siquiera sospechar mis deseos de volver… ¿Qué me has dado, vida mía, que ando triste noche y día? Rondando siempre tu esquina, mirando siempre tu casa, y esta pasión que lastima, y este dolor que no pasa. ¿Hasta cuando iré sufriendo el tormento de tu amor? Este pobre corazón que no la olvida me la nombra con los labios de su herida y ahondando más su sinsabor la mariposa del dolor cruza en la noche de mi vida. Compañeros, hoy es noche de verbena. Sin embargo, yo no puedo con mi pena y al saber que ya no está, solo, triste y sin amor me pregunto sin cesar. Lingering Around Your Corner Tonight, I feel like finding her, erasing the past and forgiving her. I no longer care what they’ll say or the gossip they’ll spread— after all, people always talk! All I think of is her, all the time. This devouring passion is unbearable. And she, always unaware, without even suspecting my desperate wish to return… What have you done to me, my love, that I wander sad night and day? Always lingering around your corner, always staring at your house, with this passion that wounds, and this pain that won’t fade. How long will I keep suffering the torment of your love? This poor heart, which can’t forget her, names her with the lips of its wounds. Deepening its bitterness, the butterfly of sorrow flits through the night of my life. Friends, tonight is a festive night, but I cannot bear my sorrow. Knowing she’s no longer here, alone, sad, and loveless, I keep asking myself, endlessly.

La abandoné y no sabía • 1943 • José Canet • Lyrics by José Canet

Amasado entre oro y plata de serenatas y de fandango; acunado entre los sones de bandoneones nació este tango. Nació por verme sufrir en este horrible vivir donde agoniza mi suerte. Cuando lo escucho al sonar, cuando lo salgo a bailar siento más cerca la muerte. Y es por eso que esta noche siento el reproche del corazón. La abandoné y no sabía de que la estaba queriendo y desde que ella se fue siento truncada mi fe que va muriendo, muriendo… La abandoné y no sabía que el corazón me engañaba y hoy que la vengo a buscar ya no la puedo encontrar… ¡A dónde iré sin su amor! Al gemir de los violines los bailarines van suspirando. Cada cual con su pareja las penas viejas van recordando. Y yo también que en mi mal sufro la angustia fatal de no tenerla en mis brazos, hoy la quisiera encontrar para poderla besar y darle el alma a pedazos… Pero inútil… Ya no puedo… Y en sombra quedo con mi ilusión. I Left Her Without Knowing Born of gold and silver, serenades and fandangos, cradled by the sounds of bandoneons— this tango was born. It was born to see me suffer through this wretched life where my luck wastes away. When I hear it play, when I dance to it, I feel death draw nearer. That’s why tonight, I feel my heart’s reproach. I left her without knowing I loved her. Since she left, my faith has been shattered, dying, slowly dying. I left her without knowing that my heart was deceiving me, and now that I’ve come to find her, I can’t find her anywhere. Where will I go without her love? As the violins wail, the dancers sigh, each one with their partner remembering old sorrows. I, too, in my grief, suffer the fatal anguish of not holding her in my arms. Today, I want to find her, to kiss her, to give her my soul in pieces. But it’s useless… I can’t… I’m left in shadows with only my illusions.

Nada más que un corazón • 1944 • Manuel Sucher • Lyrics by Carlos Bahr

Nada más que tu cariño

es lo que quiero,

es el milagro que a la vida

le reclamo como premio

por tanta herida.

Nada más que tu cariño

es lo que quiero,

pues nunca tiene por fortuna

que lograr esa ventura

de vivir para tu amor.

No puedo darte en cambio

más que un corazón sentimental

y humilde como una canción.

Podrá mi fantasía brindarte el halago

de sueños que prometen fortuna mejor,

pero yo no tengo nada, nada más

que anhelos que hacia ti me llevan,

y aunque quiera darte un mundo,

solamente puedo darte un corazón

que late con todo amor.

Nada más que tu cariño

es lo que quiero,

pues nunca tiene por fortuna

que lograr esa ventura

de vivir para tu amor.

Nothing but a Heart

All I want is your love—

the miracle I ask of life

as payment

for so many wounds.

All I want is your love—

I’ve never had the fortune

to find the joy

of living for your love.

In return,

I can only offer a sentimental heart,

humble as a song.

My dreams might offer you

flattering promises

of a better fortune,

but I have nothing, nothing

but longings that lead me to you.

Even if I wished to give you the world,

I can only give you a heart

beating with all my love.

All I want is your love—

I’ve never had the fortune

to find the joy

of living for your love.El tango es una historia • 1944 • Roberto Chanel • Lyrics by Reinaldo Yiso

En hojas de berro, con pluma de llanto,

escribió su historia aquel viejo arrabal.

Después un bohemio con alma de santo,

le puso armonía, lo hizo inmortal.

Igual que esos yuyos de humildes veredas,

que nacen un día sin causa y razón,

así nació el tango y hoy es una estrella

que brilla en el cielo de toda emoción.

El tango es una historia,

cada frase es un recuerdo,

cada parte es una vida con una pena escondida

y todo el tango es lo nuestro.

Emoción que se hace queja

en la voz del bandoneón.

El tango es siempre una historia

que tiene en todas sus hojas

palabras del corazón.

Tango Is a Story

On watercress leaves, with a pen of tears,

that old neighborhood wrote its story.

Later, a bohemian with a saintly soul

gave it harmony and made it immortal.

Like the weeds of humble sidewalks,

that sprout one day without cause or reason,

so tango was born.

Now it’s a star

shining in the sky of all emotions.

Tango is a story,

each phrase a memory,

each part a life with a hidden sorrow.

And all of tango is ours.

Emotion becomes lament

in the voice of the bandoneón.

Tango is always a story,

and in all its pages,

it holds words of the heart.© 2025 Barry Hashimoto. All rights reserved. Proprietary images and text may not be reproduced, distributed, or used in any form without the author’s permission.