Translation #1: Pugliese-Chanel 1945-1947

Decoding late Chanel through ten tangos

This essay translates and analyzes ten tangos recorded by Osvaldo Pugliese and Roberto Chanel between 1945 and 1947. By analyzing their poetic symbolism and historical context, it suggests how these works engage with the larger currents of culture and politics in Argentina. The essay also introduces new translations of their lyrics, exposing the texts beneath the music to a wider audience.

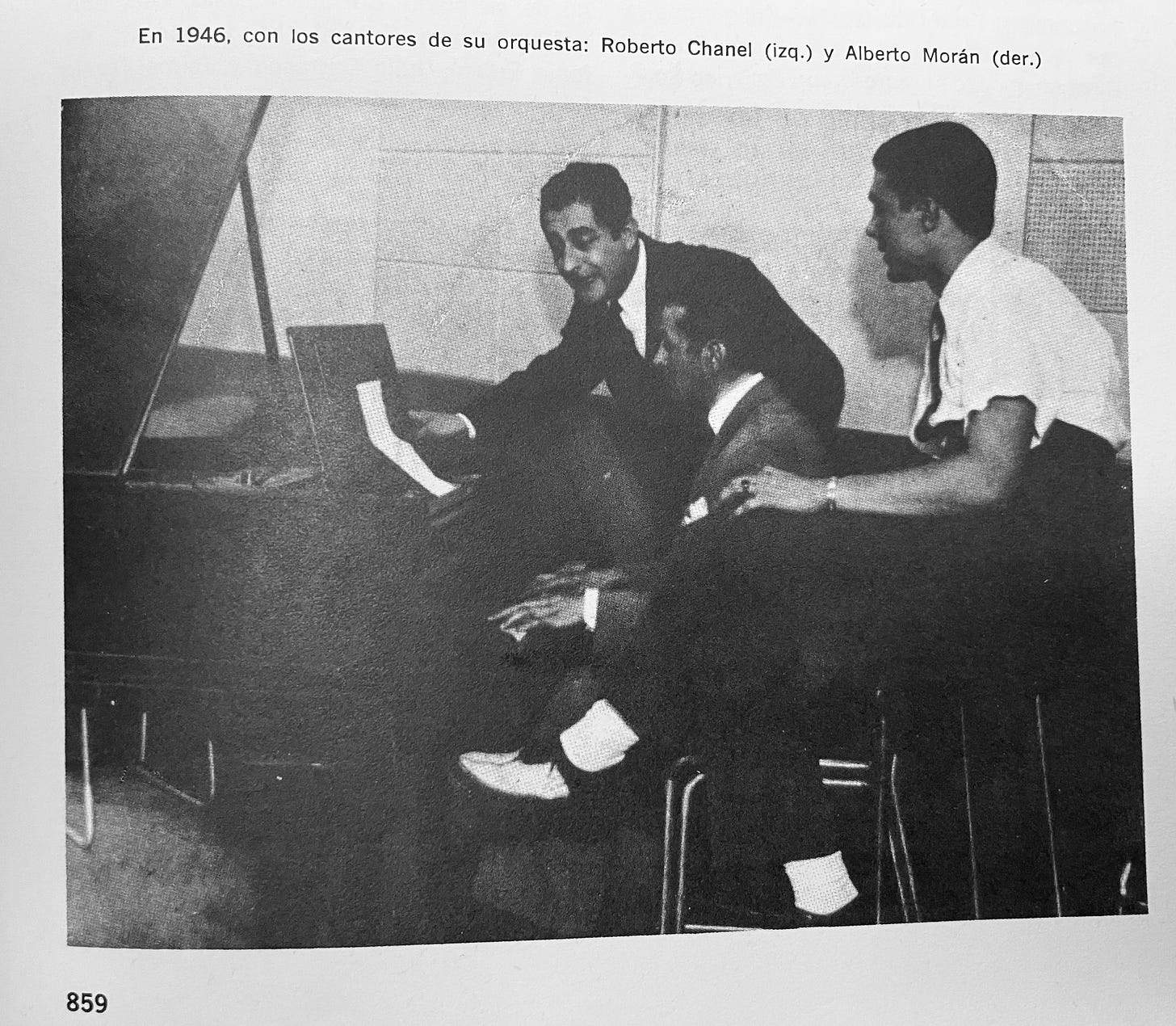

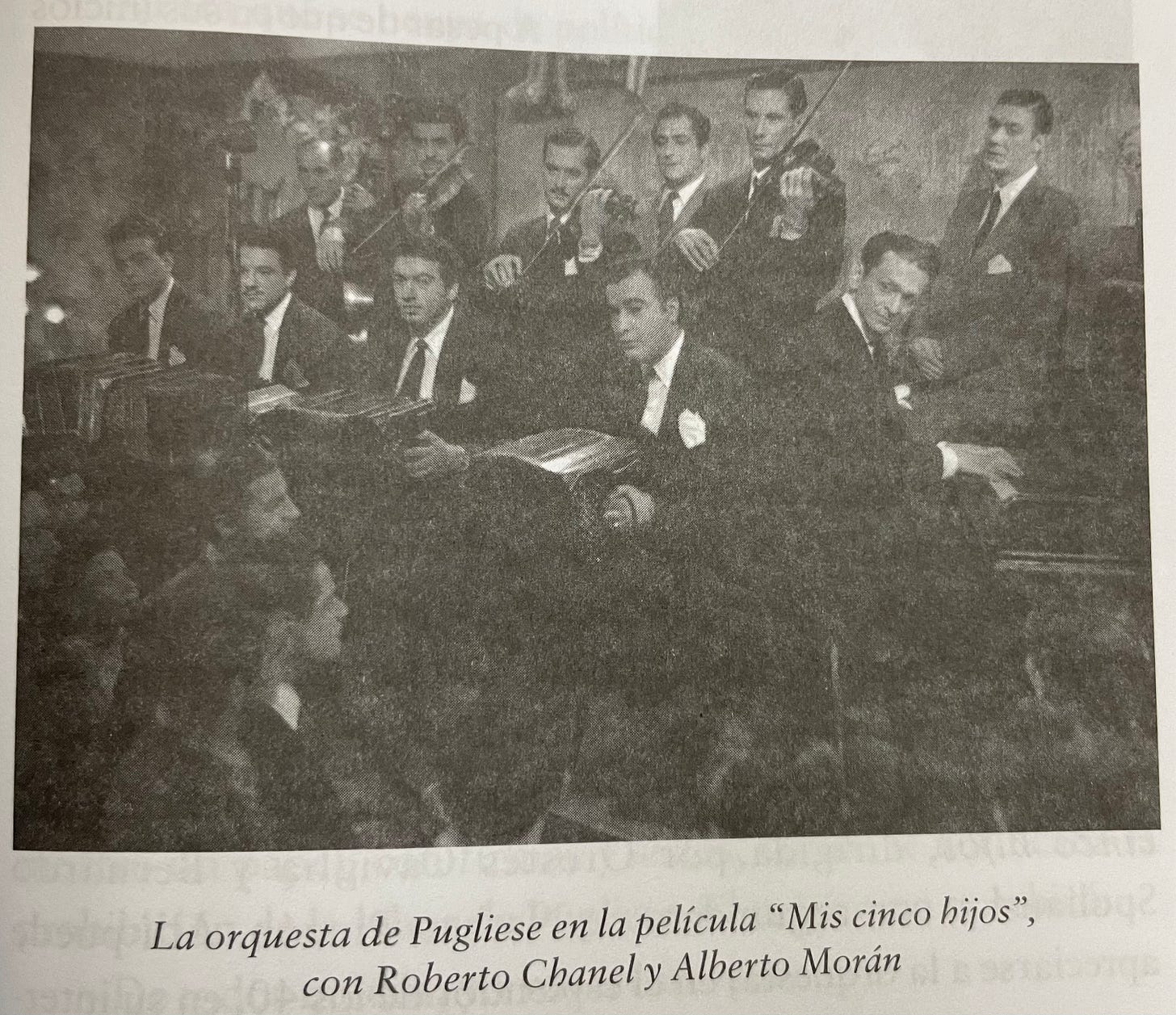

Photos: Ferrer, Horacio. El Libro del Tango: Arte Popular de Buenos Aires. Edited by Antonio Terson. 3 vols. Buenos Aires: Patrón, 1980.

Introduction

The collaboration between Osvaldo Pugliese and Roberto Chanel (1943–1947) began amid a major pivot in Argentina’s history. From 1930 onwards, the nation underwent dramatic political, social, and cultural changes, coinciding roughly with the transition from the era of tango sextets to the era of the larger orquestas típicas. These changes accelerated after the Revolution of ’43 and the ascent of a new authoritarian regime, during which Pugliese began recording.

Among the lasting legacies of the Pugliese-Chanel ouevre are ten tangos—Dandy, El Sueño del Pibe, Fuimos, Yo Te Bendigo, Sin Lágrimas, Escúchame Manón, Tiempo, La Mascota del Barrio, Cabecitas Blancas, and Ojos Maulas from the collaboration’s second half. Like the ballads of Marino, Ruiz, Podestá, Durán, Berón, and Campos, these tangos have become fractal hymns of the last hours of great milongas.

DJs often construct tandas from these tangos, choosing four to shape a distinctive mood. The tandas are intense and poignant, well-suited for advanced dancers, and demanding deep emotional engagement. Yo Te Bendigo, Dandy, and Sin Lágrimas are perennial favorites, celebrated in performances and competitions worldwide. Yet, the larger set here tells a cohesive artistic narrative that merits analysis. Through their melodies and symbolism, these songs explore universal themes of aspiration, disillusionment, and redemption, all within the charged historical setting of postwar Argentina. This essay analyzes the themes, symbols, and political resonance of these works in context.

Thematic Analysis

The tangos in this tanda are united by an exploration of desire and its interplay with loss, transformation, and memory. El Sueño del Pibe and La Mascota del Barrio explore youthful ambition through the lens of football, a powerful cultural symbol in Argentina. In El Sueño del Pibe, a boy dreams of glory, his aspirations glowing with the optimism of youth, even as they rest on the edge of fantasy. La Mascota del Barrio offers a stark counterpoint: the fall from triumph as a neighborhood hero’s career is derailed by injury. Yet, the song resists despair, portraying the boy’s eventual return to dignity and the embrace of his community. These narratives reflect not only individual longing but also a society dealing with the dislocations of urbanization and class mobility.

Ambition’s darker side emerges in Dandy, where vanity and betrayal are exposed with biting disdain. The dandy struts as a self-made swell, but the poet reveals him as a “gran batidor”—a big rat, a snitch—whose café companions will abandon him once his treachery is uncovered. The song’s scorn is sharpened by its contrasts: the fleeting glamour of social ambition against the enduring sacrifices of family. The imagery of the street, once a space of camaraderie, becomes a theater of humiliation, while the workshop, where the dandy’s sister toils with devotion, stands as a symbol of unpretentious virtue. This juxtaposition underscores a moral critique of superficial aspirations, resonating with the anxieties of two societies in flux during the years just prior to the 1930 coup d’etat, when the poetry was written, and the years just after the 1943 coup d’etat, when Chanel and Pugliese recorded the song with Estudio Odeon, the premier outfit of the day utilizing superior microphones and sound engineering.

Love, central to tango’s poetic tradition, appears here in its many forms, from romantic yearning to familial devotion. Fuimos mourns the collapse of a shared dream, its vivid imagery—“I was like a rain of ash and weariness”—capturing the hollow aftermath of love lost. The speaker insists on separation, even as their pain remains unresolved, embodying tango’s power to articulate the tension between resolve and vulnerability. Sin Lágrimas exudes stoic grief, as the speaker declares, “Why cry for what’s already lost?” This pride, however, is undercut by a plaintive wish—“please, let you never suffer as I have suffered”—exposing tenderness beneath defiance.

Where Fuimos and Sin Lágrimas linger in resignation, Ojos Maulas seethes with betrayal. The song’s treacherous gaze mirrors the duplicity of an unfaithful lover, whose “two false eyes” stare back at a young man undone by her. The speaker’s lament interweaves memories of innocent joy—“You kissed me once, and I kissed you a thousand times”—with the bitterness of trust betrayed. Here, the guitars “weeping their soft chords” and the campfires’ “illusion of light” create a haunting contrast to the disillusionment that follows. Ojos Maulas extends tango’s exploration of love’s fragility, capturing the persistent grief of betrayal, even betrayal by a mere country girl.

Forgiveness and redemption take on an almost cosmic dimension in Yo Te Bendigo, where the speaker transforms their anguish into an act of grace. The imagery of blessings ascending to the stars lifts the personal into the universal, echoing the spiritual undercurrents often present in tango’s lyricism. By contrast, Escúchame Manón explores love’s tension between longing and jealousy, its plea for reconciliation tinged with a liminal anguish. The titular Manón is a clear nod to Manon Lescaut, the tragic heroine of French literature and opera, adding layers of allusion to the enigmatic and unattainable lover, whose mystery deepens the song.

Filial devotion takes center stage in Cabecitas Blancas, a tender homage to maternal sacrifice. The song’s reverence for elderly mothers—those who carried the burdens of the household without complaint—honors the heroism of everyday life. The home becomes not just a physical refuge but a repository of memory and morality. Unlike the hollow glamour of the dandy’s pursuits, Cabecitas Blancas honors familial love as a stabilizing force amidst personal and societal turmoil.

Imagery of light and shadow amplifies the emotional landscapes of these songs, deepening their resonance. The youthful brightness of El Sueño del Pibe contrasts with the twilight regret of Fuimos and Sin Lágrimas, where fading light reflects love’s end and the encroachment of loss. Ojos Maulas uses campfire light and the weeping of guitars to underscore the tension between fleeting joy and the bitterness of betrayal. Celestial imagery in Yo Te Bendigo transforms personal suffering into something timeless, while Cabecitas Blancas casts its subjects in a warm glow of reverence. Even silence holds meaning: in Tiempo, the absence of music evokes the passage of years, while the overgrown garden becomes a metaphor for the persistence of memory amidst decay.

Spaces in these tangos are imbued with emotional weight. The street in Dandy, once a site of community, becomes a stage for the protagonist’s shame, while the home in La Mascota del Barrio offers a sanctuary of hope. Ojos Maulas situates its betrayal in an archetypal rural landscape of kitchens and campfires, weaving intimacy and treachery together. In Cabecitas Blancas, the home transcends its materiality, embodying the enduring power of love and memory. Together, these sensory and spatial motifs weave a tapestry that speaks to universal human experiences while remaining grounded in the particulars of Argentine life. The tanda thus offers not just narratives of loss and redemption but a reflection on the struggles and aspirations of people in Buenos Aires.

Photo: Ferrer, 1980.

Historical Interpretations: Art, Politics, and Postwar Argentina

It is impossible to say, at this distance from Pugliese and any authentic records or other clear-cut evidence of his beliefs and motives, what motivated his orchestra’s choice to record these particular songs. Some of the lyrics appear to have been commissioned specifically to accompany the compositions and arrangements. Others were long decades before Chanel met Pugliese, and were selected for reasons that will probably remain unclear. Speculation on Pugliese’s intentions must remain provisional.

However, we can (a fortiori, we should) turn to interpretive techniques in the field of political theory to interpret these works. Quentin Skinner’s Visions of Politics and Leo Strauss’s Persecution and the Art of Writing provide complementary interpretive frameworks for examining the historical and esoteric dimensions of Pugliese’s music. Skinner encourages us to situate these tangos within their cultural and political context, asking how they reflect the anxieties and debates of mid-20th-century Argentina. Strauss, meanwhile, invites us to consider how veiled critiques may have been embedded in these works, shaped by the constraints of political repression.

Recorded between 1945 and 1947, Pugliese’s nine tangos reflect the aspirations and disillusionments of a society in flux. These years followed the 1943 coup d’état, which ended the corruption of the Infamous Decade but introduced new ideological and social fractures. The coup’s nationalist architects, including Juan Domingo Perón, sought to reshape Argentine society, co-opting the working class through populist reforms while repressing leftist factions. As Minister of Labor, Perón built loyalty among workers with wage increases and labor protections, but he simultaneously marginalized communist unions, surveilled opponents, and consolidated power, paving the way for his eventual dominance of Argentine politics and porteño political life. Pugliese, a Marxist since a young age and member of Argentina’s communist party since 1936, found himself alienated by this populist-nationalist agenda, which he viewed as a betrayal of the internationalist ideals he not only subscribed to, but publicly championed.

The period’s political and social dynamics permeate Pugliese’s music. Central to many of these tangos is the theme of thwarted aspiration. Fuimos, for example, appears on the surface to mourn the end of a romantic relationship: “We were the hope that never arrived, that could not glimpse a calm evening.” Yet this line resonates beyond the personal, reflecting the fragmentation of the left in the wake of Perón’s rise. The traveler who “lay down to die” becomes a metaphor for the deferred dreams of a working class whose autonomy was subordinated to state control.

Similarly, La Mascota del Barrio mirrors the broader tragedy of political exclusion. The story of a sidelined football player—“The team’s best player, stolen by fate, never came home on their shoulders again”—parallels the marginalization of those excluded from Perón’s tightly managed labor vision. The lyric’s conclusion, “A hero on Sundays, now only a memory in the stands,” captures the bitterness of being cast aside, whether on the grassy field or in the struggle for workers’ rights.

Sin Lágrimas intensifies these themes of betrayal and ideological fracture. Its mournful declaration—“This music will strike you deep, wherever your betrayal hears it play”—initially suggests personal heartbreak. Yet, as Strauss would note, political critique often lies beneath such surfaces. For Pugliese, betrayal could symbolize Perón’s co-option of class struggle to consolidate personal power, leaving Marxist revolutionaries disillusioned and divided.

At the same time, Pugliese’s tangos offer moments of grace and redemption. Yo Te Bendigo transforms personal pain into a gesture of cosmic reconciliation: “The soul that suffered for you offers you its blessing.” The act of blessing becomes a defiant affirmation of human connection, even amid political and ideological despair. Meanwhile, Cabecitas Blancas shifts focus from political struggles to filial love, reverently portraying mothers as stabilizing figures in a fractured world. The lyric’s acknowledgment of belated gratitude—“I kissed their white-haired heads and begged forgiveness for the tenderness I never gave”—reflects not only personal remorse but also the enduring dignity of those who sacrificed for others, often going unrecognized.

Particularly striking is Dandy, which initially appears as a satirical critique of a vain, superficial man. However, the lunfardo term batidor—a slang term for an informer—embedded in the song’s subtext reveals a darker meaning. The protagonist, seemingly just feckless figure to pity, in fact embodies the treachery of those who betrayed comrades under political repression. “You strutted down the boulevard, proud of your elegance, but your shadow hid the truth—a coward who sold his friends,” the lyric proclaims. This Straussian reading repositions Dandy as a biting condemnation of batidores, whose collaboration with authoritarian power undermined solidarity and resistance. The dandy is a rat, Chanel informs us with disdain beneath his sweet, crooning voice.

Through these tangos, Pugliese confronts the ideological fractures and personal betrayals of his time. His music reflects the struggles of a nation where solidarity was both celebrated and eroded, and where the boundaries between personal and political loss became blurred. Whether viewed as historical artifacts or veiled critiques, these works endure as meditations on aspiration, disillusionment, and redemption in a turbulent time.

Photo: Ferrer, Horacio. El Libro del Tango: Arte Popular de Buenos Aires. Edited by Antonio Terson. 3 vols. Buenos Aires: Patrón, 1980.

The Poetry and Translations

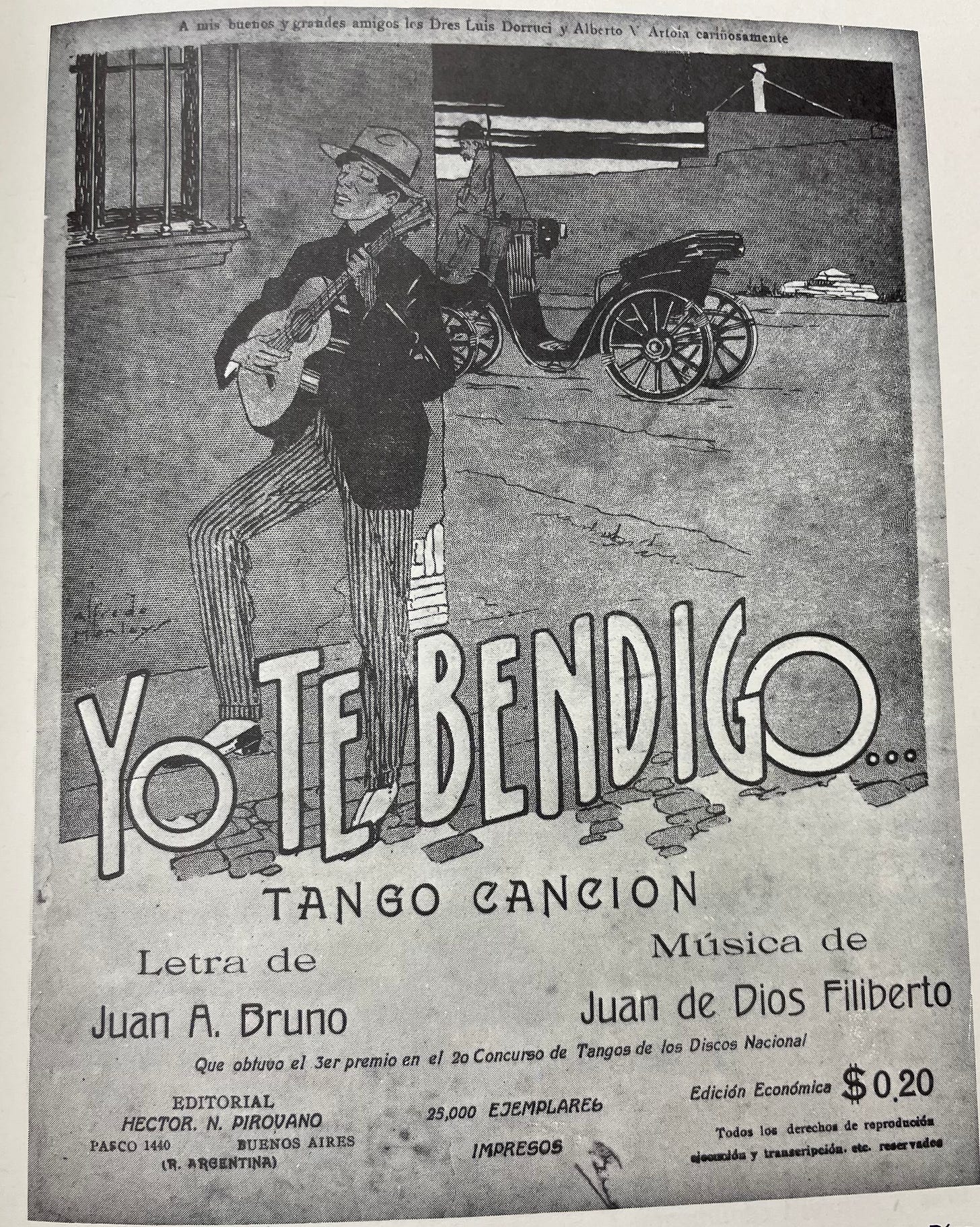

The nine tangos recorded by Osvaldo Pugliese between 1945 and 1947 reflect the brilliance of tango’s finest poets and composers. Homero Manzi (1907–1951) wrote the lyrics for Fuimos, paired with music by José Dames (1913–1994). Sin Lágrimas was written by José María Contursi (1911-1972), with music by Carlos José Pérez (a.k.a. “Charlo,” 1906-1990). Juan de Dios Filiberto (1885–1964) composed Yo Te Bendigo to lyrics by Juan Andrés Bruno. Escúchame Manón was created by Francisco Pracánico (1898–1971), Roberto Chanel (1914–1972), and Claudio Frollo. El Sueño del Pibe combines music by Juan Puey with lyrics by Alfredo Reinaldo Yiso (1918–1982). Dandy features Lucio Demare (1906–1974), Agustín Irusta (1903–1987), and Roberto Fugazot (1902–1971). Tiempo, by Osvaldo Ruggiero (1922–1994) and Francisco García Jiménez (1899–1983), and La Mascota del Barrio by Abel Aznar (1913–1983) and Yiso, complete the list alongside Cabecitas Blancas, composed by Alberto Pugliese (1910–1981) with lyrics by Enrique Dizeo (1893–1980).

All original lyrics in this analysis are sourced from TodoTango. For a full discussion of my translation methodology and its guiding principles, see Translating Tango: A New Approach elsewhere on this blog.

Fuimos • 1945 • José Dames • Lyrics by Homero Manzi

Fui como una lluvia de cenizas y fatigas

en las horas resignadas de tu vida...

Gota de vinagre derramada,

fatalmente derramada, sobre todas tus heridas.

Fuiste por mi culpa golondrina entre la nieve

rosa marchitada por la nube que no llueve.

Fuimos la esperanza que no llega, que no alcanza

que no puede vislumbrar su tarde mansa.

Fuimos el viajero que no implora, que no reza,

que no llora, que se echó a morir.

¡Vete...!

¿No comprendes que te estás matando?

¿No comprendes que te estoy llamando?

¡Vete...!

No me beses que te estoy llorando

¡Y quisiera no llorarte más!

¿No ves?,

es mejor que mi dolor

quede tirado con tu amor

librado de mi amor final

¡Vete!,

¿No comprendes que te estoy salvando?

¿No comprendes que te estoy amando?

¡No me sigas, ni me llames, ni me beses

ni me llores, ni me quieras más!

Fuimos abrazados a la angustia de un presagio

por la noche de un camino sin salidas,

pálidos despojos de un naufragio

sacudidos por las olas del amor y de la vida.

Fuimos empujados en un viento desolado...

sombras de una sombra que tornaba del pasado.

Fuimos la esperanza que no llega, que no alcanza,

que no puede vislumbrar su tarde mansa.

Fuimos el viajero que no implora, que no reza,

que no llora, que se echó a morir.

We Were

I was like a rain of ash and weariness

in the resigned hours of your life.

A drop of vinegar spilled—

spilled, irreparably—

on all your wounds.

You, because of me,

were a swallow in the snow,

a wilted rose under a rainless cloud.

We were a hope that never arrived,

that could not glimpse a calm evening.

We were a traveler who didn’t pray,

didn’t beg, didn’t weep—

who lay down to die.

Go.

Can’t you see you’re killing yourself?

Can’t you see I’m calling you back?

Go.

Don’t kiss me; I’m crying for you,

and I’d rather never cry again.

Don’t you see?

It’s better this way—

to let my pain

fall away with your love.

Go.

Don’t you understand?

I’m saving you.

I’m loving you.

Don’t follow me,

don’t call me,

don’t kiss me,

don’t cry for me,

don’t love me anymore.

We clung to a foreboding,

on the night of a path with no way out.

Shadows of a shadow—

remnants of a wreck—

tossed by the waves of love and life.

We were cast into a desolate wind.

We were the hope that never arrived,

that could not glimpse a calm evening.

We were a traveler who didn’t pray,

didn’t beg, didn’t weep—

who lay down to die.Yo Te Bendigo • 1925 • Juan de Dios Filiberto • Lyrics by Juan Andrés Bruno

Daba la diana el gallo, ladrando un perro desde lejos contestó y el arrabal al despertar al nuevo día saludó... Lejos pasaba un coche... Cual centinela que la guardia terminó, la luz temblona de un farol como un lamento se apagó. Rompió el silencio el bordonear de la guitarra y por sus cuerdas el dolor pasó llorando y una voz que la pena desgarra cantó de este modo su cruel dolor: ¡Yo te bendigo pese al daño que me has hecho aunque otros brazos te acaricien y te abracen, pues el rencor no ha cabido en el pecho que un día llenaste de luz y de amor!... Mas si con dolor llegas a llorar al recuerdo del amor que te supe dar piensa que te perdonó mi corazón y el alma que por ti sufrió te da su bendición. Daba la diana el gallo. Como un reproche a la amorosa bendición ladraba el perro y de un farol murió la luz con la canción... Pero el yo te bendigo que desde el fondo de su pecho él arrancó de la guitarra al cielo fue y en una estrella se escondió... Blessing You The rooster called out at dawn, and from the distance, a dog barked back. The neighborhood stirred awake, greeting the new day. A carriage passed by, and like a sentinel done with his watch, the flickering light of a streetlamp faded into a sigh. The silence broke with the murmur of a guitar, its strings echoing grief. A voice, raw with sorrow, sang its anguish like this: “I bless you, despite the hurt you’ve done me. Even if other arms now hold and caress you, resentment never found its way into the heart you once filled with light and love. But if someday, struck by sorrow, you weep for the memory of the love I gave you, remember this: my heart forgave you, and the soul that suffered for you offers you its blessing.” The rooster called out at dawn, and a dog barked again, as though rebuking the blessing. The streetlamp’s light died with the final notes of the song. But the words I bless you, wrenched from the depths of his heart, rose from the guitar to the heavens and hid itself among the stars.

Sin Lágrimas • 1941 • Charlo • José María Contursi

No sabes cuánto te he querido, como has de negar que fuiste mía; y sin embargo me has pedido que te deje, que me vaya, que te hunda en el olvido. Ya ves, mis ojos no han llorado, para qué llorar lo que he perdido; pero en mi pecho desgarrado... sin latidos, destrozado, va muriendo el corazón. Ahora, que mi cariño es tan profundo, Ahora, quedo solo en este mundo; qué importa que esté muriendo y nadie venga a cubrir estos despojos, ¡qué me importa de la vida! Si mi vida está en tus ojos. Ahora que siento el frío de la muerte, ahora que mis ojos no han de verte... qué importa que otro tenga tus encantos, si yo se que nunca nadie puede amarte tanto, tanto como yo te amé. No puedo reprocharte nada si encontré en tu amor la fe perdida; con el calor de tu mirada diste fuerzas a mi vida, pobre vida destrozada. Y, aunque mis ojos no han llorado, hoy, a Dios rezando le he pedido... que si otros labios te han besado, y al besarte te han herido, que no sufras como yo. Without Tears You’ll never know how much I loved you, how can you deny you once were mine? Yet still, you’ve asked me to leave, to vanish, to bury you in oblivion, to erase it all. But look, my eyes have shed no tears. Why cry for what’s already lost? Still, inside this torn-open chest, my heart, shattered, lifeless, is quietly dying. Now—when my love runs deepest, when I am left utterly alone in this world— what does it matter if I’m dying, if no one comes to cradle these remains? What do I care for life? My life lives only in your eyes. Now—when I feel the chill of death, when I know my eyes will never see yours again— what does it matter if another owns your charms? I know no one could ever love you as deeply, as endlessly, as I have. I cannot reproach you for anything. In your love, I found a lost faith. The warmth of your gaze gave strength to this broken, wrecked life. And though my eyes have shed no tears, today, praying to God, I asked Him— if other lips have kissed you and hurt you in their touch— please, let you never suffer as I have suffered.

Escúchame Manón • 1947 • Francisco Pracánico • Lyrics by Roberto Chanel and Claudio Frollo

Cuando sepas que mi amor está lleno de verdad

tu temor, tu indiferencia, pasarán.

El cariño que por ti en mi pecho se anidó,

¿no te apenas que se muera de dolor?

Ronda mis noches tu ondulada melenita

y me acaricia la dulzura de tu voz.

Mientras la luz que se refleja en tus pupilas

me dice, es tuyo mi corazón.

Escuchame Manón y dejate querer,

aleja tu tenaz preocupación, tu padecer.

Es nuestro el porvenir, lo veo en tu mirar,

mis esperanzas de amar las veo en ti.

Vuelven mis sueños, apareces vida mía,

y me reprocha la tristeza de tu voz.

Siento en mi alma la tortura de los celos

y sufre mucho mi corazón.

Listen to Me, Manón

When you see the truth of my love,

your fear, your indifference,

will vanish like morning mist.

The love that nested in my chest—

don’t you pity it,

as it dies of sorrow?

Your rippling hair haunts my nights,

your voice grazes my dreams,

and the light that lives in your eyes

whispers, “Your heart is mine.”

Listen to me, Manón, and let me love you.

Cast aside the shadows of doubt and pain.

The future is ours—I see it in your gaze.

All my hopes, all my love, live in you.

You appear again in my dreams, my life,

and your sorrow-laden voice

reproaches me.

Jealousy cuts through my soul,

and my heart suffers deeply, endlessly.El Sueño del Pibe • 1931 • Juan Puey • Lyrics by Alfredo Reinaldo Yiso

Golpearon la puerta de la humilde casa, la voz del cartero muy clara se oyó, y el pibe corriendo con todas sus ansias al perrito blanco sin querer pisó. "Mamita, mamita" se acercó gritando; la madre extrañada dejo el piletón y el pibe le dijo riendo y llorando: "El club me ha mandado hoy la citación." Mamita querida, ganaré dinero, seré un Baldonedo, un Martino, un Boyé; dicen los muchachos de Oeste Argentino que tengo más tiro que el gran Bernabé. Vas a ver que lindo cuando allá en la cancha mis goles aplaudan; seré un triunfador. Jugaré en la quinta después en primera, yo sé que me espera la consagración Dormía el muchacho y tuvo esa noche el sueño más lindo que pudo tener; El estadio lleno, glorioso domingo por fin en primera lo iban a ver. Faltando un minuto están cero a cero; tomó la pelota, sereno en su acción, gambeteando a todos se enfrentó al arquero y con fuerte tiro quebró el marcador. The Boy’s Dream They knocked on the door of the humble house. The postman’s voice rang sharp and clear. The boy raced to the door, all excitement, his bare feet scrambling, stepping on the little white dog by mistake. “Mama, Mama,” he shouted, his voice bursting through the house. His mother, surprised, left the washtub. Laughing and crying, he yelled, “The club—they’ve sent me a letter! It’s here!” Mama, darling Mama, I’ll bring home the big checks, I’ll be Baldonedo, Martino, Boyé. The kids at Oeste Argentino say I’ve got more fire than Bernabé. Just wait, you’ll see me on the field. The cheers will be mine. I’ll play in the juniors, then the big leagues. They’ll crown me a champion. That night, the boy dreamed the sweetest dream— a Sunday, the stadium roaring, and there he was, playing first team for the first time. The score was tied in the final minute. He took the ball, calm as can be, dodged past everyone, stood face to face with the goalkeeper, and with a shot like lightning, he shattered the tie.

Dandy • 1928 • Lucio Demare • Lyrics by Agustín Irusta and Roberto Fugazot

Dandy, ahora te llaman los que no te conocieron cuando entonces eras terrán, porque pasás por niño bien y ahora te creen que sos un gran bacán; mas yo sé, dandy, que sos un seco, y en el barrio se comentan fulerías, para tu mal... Cuando sepan que sos confidente, tus amigos del café te piantarán. Has nacido en una cuna de malevos, calaveras, de vivillos y otras yerbas... Sin embargo, ¡quién diria!, en el circo de la vida siempre fuistes un chabón. Entre la gente del hampa no has tenido performance, pero dicen los pipiolos que se ha corrido la bolilla y han junado que sos un gran batidor... Dandy, en vez de darte tanto corte pensá un poco en tu viejita y en su dolor. Tu pobre hermana en el taller su vida entrega con entero amor y por las noches su almita enferma, con la de su madrecita en una sola sufriendo están... Pero un dia, cuando nieve en tu cabeza, a tu hermana y a tu vieja llorarás. Dandy Dandy, now they call you that, the ones who never knew you back when you were just a nobody. Now you strut around like a proper swell, a big shot they all believe. But I know the truth, Dandy— you’re broke. And in the old neighborhood, they’re whispering all kinds of things to your shame. When they find out you’re a snitch, your café pals will leave you cold. You were born into a crib of tough guys, reckless drifters, and slick cheats, a cradle full of trouble. Still, who would have thought? In life’s big circus, you’ve always been a fraud. In the underworld, you never made your mark, but the word’s out now— the kids are talking. Everyone knows you’re just a big rat. Dandy, instead of playing the part, think a little about your poor old mother and her pain. Your sister slaves away at the workshop, giving her life with pure love. And at night, her sick little soul, together with your mother’s, suffers as one. But one day, when snow settles on your head, you’ll weep for your sister and your mom.

Tiempo • 1946 • Osvaldo Ruggiero • Lyrics by Francisco García Jiménez

¿Dónde están sus ojos? ¿Dónde su sonrisa? ¿Dónde está el camino que la trajo a mí? ¿Y el aroma leve y el sol y la brisa? ¿Sombras en las sombras tristes del jardín? Tiempo de alegría... ¿Dónde has terminado? Tiempo de agonía... ¿Todo se acabó? Hoy acaso sea necio y trasnochado que estos versos grises lloren por su amor. Tiempo eterno de vaivenes, tiempo eterno... ¿Para qué tus primaveras? Para qué. Siempre el paso del fantasma del invierno por la casa desalada escucharé... Todo tiempo será tiempo de congojas, sin sus ojos, sin su risa, sin su amor... Toda música, rumor de secas hojas... Toda voz, el eco turbia de su adiós... Lejos su sonrisa... lejos ya sus ojos... Sombras en las sombras del atardecer. Se cubrió el camino de yuyos y abrojos, ella y mi esperanza nunca han da volver. Todo es un recuerdo pálido y lejano. Todo como el eco turbio de un adiós. Pobres ilusiones... Pobres sueños vanos... Tiempo, fue tu mano quién la muerte dio. Time Where are her eyes? Where is her smile? Where is the path that once brought her to me? And the faint perfume, the sun, the breeze? Shadows upon shadows in the garden’s sorrowful gloom. Time of joy… Where have you ended? Time of anguish… Has it all been swept away? Today, perhaps it’s foolish and out of place that these gray verses weep for her love. Eternal time of ebb and flow, eternal time… What were your springs for? What purpose did they serve? Always I will hear the ghostly steps of winter wandering through the desolate house. All time will be a time of sorrow, without her eyes, without her laughter, without her love. All music, the dry rustle of brittle leaves. Every voice, the murky echo of her farewell. Far away, her laughter… Far away, her eyes… Shadows within shadows at dusk. The path is overrun with weeds and thorns. She, and my hope, will never return. All is a pale, distant memory. Everything, like the murky echo of a goodbye. Poor illusions… Poor, futile dreams… Time—it was your hand that dealt the final blow.

La Mascota del Barrio • 1946 • Abel Aznar • Lyrics by Reinaldo Yiso

Del club Once Estrellas era el "centrofobal",

prometía el pibe ser un Bernabé.

Todos los domingos en andas volvía,

los goles del triunfo los hacía él.

Pero fue en una tarde, fatal esa tarde,

en una jugada su pierna quebró

y el mejor del cuadro, destino cobarde,

en andas al barrio nunca más volvió.

Un lindo domingo,

un sillón con ruedas,

un pibe que espera

con mucha ansiedad.

Que lindo domingo,

y juega su cuadro

contra el "Once de Agosto",

su eterno rival.

Muchachos que pasan,

saludan al pibe.

El pobre sonríe,

quisiera gritar.

Se van y, el que fuera

mascota del barrio,

mirando su pierna

se pone a llorar.

Vuelven los muchachos con pena en los ojos,

el cuadro Once Estrellas su invicto perdió,

le dicen al pibe con mucha tristeza,

si hubieras jugado no errás ese gol.

Y pasado un tiempo, un lindo domingo,

el pibe dejaba, por fin, el sillón.

Iba a ser de nuevo mascota del barrio,

iba a ser de nuevo el gran goleador.

The Mascot of the Neighborhood

He was the star at Club Once Estrellas,

the kid with a future, bound for fame.

Another Bernabé, they all said.

Every Sunday, he’d be carried home high,

the hero who scored the winning goals.

But then, that cursed afternoon—

a bad play, a break—his leg snapped.

The team’s best player, stolen by fate,

never came home on their shoulders again.

A Sunday rolls in,

a chair with wheels.

The boy sits, waits,

his heart full of hope.

It’s a grand Sunday—

his team’s up against

Once de Agosto,

their eternal foe.

The boys pass by,

calling out to the kid.

He smiles, barely,

choking on a cheer.

They leave, and he sits,

the mascot no more,

his eyes drop to his leg—

and the tears flow.

Later, the boys come back,

their faces heavy with loss.

Once Estrellas lost its streak today.

They tell him, quiet and low,

“If you’d been there, you’d have sunk that goal.”

Time passes. A better Sunday dawns.

The boy, finally free of his chair,

steps out, ready to play again—

ready to be the star, the scorer, the mascot once more.Cabecitas Blancas • 1947 • Alberto Pugliese • Lyrics by Enrique Dizeo

Hoy me levanté con ganas

de darle a mi corazón,

el gusto de hacer un tango

que en sus acordes porteños,

lleve engarzado el amor

de las madres que se fueron

y que junto a Dios están.

Para que sepan que un hombre

que quiso mucho a la suya

no las olvida jamás.

Un tango en el que esté

el recuerdo sacrosanto

de las que llevaron siempre

todo el peso del hogar

y que cuando la tenemos

no la sabemos cuidar.

Un tango en el que esté

el recuerdo más sublime

de esas cabecitas blancas,

que le han dado al hijo ingrato

el perdón y la caricia

que nadie les puede dar.

Hoy me levanté con ganas

de darle a mi corazón

lo que me pidió llorando

y lo hice como he podido,

pero con veneración.

Para las madres que se fueron

y que junto a Dios están.

Para que sepan que un hombre

que quiso mucho a la suya

no las olvida jamás.

Little White Heads

Today I woke with a longing

to give my heart the joy

of creating a tango,

one whose porteño chords

would carry the love

of the mothers who have gone,

who now rest at God’s side.

To let them know that a man

who loved his own dearly

will never forget them.

A tango that holds

the sacred memory

of those who bore the weight

of the household always,

and who, while with us,

we fail to cherish.

A tango to cradle

the most sublime memory

of those white-haired heads,

who gave the ungrateful son

forgiveness and a tenderness

no one else could ever offer.

Today I woke with a longing

to grant my heart its tearful wish,

and I did so as best I could,

but with deep reverence.

For the mothers who have gone,

who now rest at God’s side.

To let them know that a man

who loved his own dearly

will never forget them.Ojos Maulas • 1931 • Luis Bernstein • Lyrics by Alfredo Faustino Roldán

Lloran las guitarras con suaves acordes

arden los fogones su luz de ilusión,

y hay dos ojos maulas que miran traidores,

a un mozo tostao más lindo que el sol.

Él sabe el misterio que guarda en el pecho

la infiel paisanita que lo trastornó

y canta empañado de pena sus versos,

los tristes recuerdos de un día de amor.

Fue una mañanita te acordás mi china,

cuando la puntita del sol asomó

te encontré solita, allá en la cocina,

vos me diste un beso y mil te di yo.

Te acordás mi china que amor nos juramos

y nos abrazamos con alma y pasión,

y después que pronto se hicieron cenizas

las dulces caricias de aquella ilusión.

Escucha mis quejas y luego decime,

sin han habido causas pa' hacerme traición

y dejar que sufra y así me resigne

maneando los gritos de mi corazón.

Pero que voy a hacerle si se marchitaron

las lindas violetas que un día te di

y al dirse los pobres en mi alma dejaron

un puñao de angustias que gimen así.

Treacherous Eyes

The guitars are weeping their soft chords,

campfires flare with their illusion of light,

and there—two false eyes, full of betrayal,

gaze at a bronzed lad, handsomer than the sun.

He knows the secret hidden in her chest,

the cheating country girl who’s driven him mad.

His voice chokes on sorrow as he sings his verses,

the bitter memories of a day of love.

Do you remember, my Chinese one, that morning?

When the sun’s first point of light broke the sky?

I found you there, alone, in the kitchen—

you kissed me once, and I kissed you a thousand times.

Do you remember, my Chinese one, how we swore our love?

How we held each other with soul and passion?

And how quickly it all burned to ashes,

the sweet caresses of that fragile dream?

Listen to my lament, then tell me straight:

was there ever reason to betray me so?

To leave me to suffer, to silence my cries,

to muffle the screaming of my broken heart?

But what can I do, now the violets have withered,

those lovely violets I gave to you once?

When they died, they left in my soul a heap of anguish,

and their silent grief sobs on like this.© 2025 Barry Hashimoto. All rights reserved. Proprietary images and text may not be reproduced, distributed, or used in any form without the author’s permission.