From Bootlegs to Brilliance

The case for high-fidelity Argentine tango

Photo: From Ferrer, Horacio. El Libro del Tango: Arte Popular de Buenos Aires. Edited by Antonio Terson. 3 vols. Buenos Aires: Patrón, 1980.

1. Introduction

The era of tango DJs relying on bootlegged libraries filled with low-fidelity tracks is fading. Yet too many DJs still use these flawed collections, narrowing their selections to the best-preserved tracks while vast swaths of danceable golden-age tango remain unheard. Not because the music is unsuitable for dancing, but because the only versions available are unlistenable. Unheard and thus unfamiliar to dancers, they slip into obscurity.

Even the music that is played suffers, heard through a glass darkly—warped, flattened, stripped of its full power. The silky weight, razor phrasing, and emotional crescendos are subdued. Subtle instrumentation gets smeared. The uncanny dialogue between some of the finest-crafted bandoneóns, violins, pianos, and basses ever played—smothered. Not totally lost, but ghost-like. These recordings have been compromised not only by time, but by error and indifference.

This essay is about why that happens and what can be done about it.

If you know a tango DJ who has received their tango collection gratis—whether from a friend, a hard drive swap, or the dark web—encourage them to read this essay. Ditto for the growing number of DJs using Spotify. And if you’re a DJ, an organizer, or a dancer struggling to see why this matters—this piece is written for you.

As Francisco García Jiménez said in “Siga el Corso”: the show must go on—but the standard of DJing has evolved. Today’s high-fidelity restorations offer a superior alternative, built on a production chain that begins with archival-quality analog sources and results in digital files largely free from unnecessary distortions.

The facts and opinions I present here are drawn from decades of experience. This includes over thirty years of listening to Argentine tango, twenty of dancing and DJing, and the research of those who have studied this issue systematically—namely, the detailed release notes from Tango Time Travel and Tango Tunes, the exhaustive cataloging of Bernhard Gehberger, and the research and writing of Frank Jin and Michael Lavocah. Their contributions, alongside my own experience and research, provide the foundation for understanding the problem—and for envisioning a better future for tango DJing.

1.1 Musical Selection and Audio Fidelity

Nothing in this essay diminishes the vital role of musical selection in DJing. Crafting the right sequence of songs—balancing orchestras, singers, and arrangements while attuning to the particular crowd, venue, and moment—remains a crucial albeit highly subjective art. The narrative arc of a milonga can shift with the specific mix of patrons, the ratio of local to traveling dancers, and so on. Reasonable people will disagree on precisely how to shape and pace the music of any milonga; indeed, these creative choices define the individuality of each DJ.

By contrast, audio quality operates on a more objective plane. Regardless of how one constructs a musical narrative throughout the session, clear, well-transferred recordings enhance everyone’s experience. One can debate which tracks of the main orquestas to prioritize, which era (indeed, if any) of Canaro’s tango should be played, and what to play as the last two tandas of an evening. However, no reasonable person contests the merit of a clean signal, free from distortion and muffled frequencies. In short, the selection of music is a creative realm where diversity and disagreement thrive, whereas ensuring high-quality audio is a technical goal on which nearly all can agree.

1.2 Two Distinct Sources of Degradation

Tango recordings have long suffered from two distinct but compounding issues. First, transfer artifacts arise when legacy analog media—whether fragile shellac, timeworn vinyl, or reel-to-reel tape—are converted to digital form. This process can introduce pitch drift, mechanical noise, misapplied equalization, and excessive reverb, distorting the music’s original character. Second, compression artifacts emerge when these already compromised transfers are subjected to lossy encoding, stripping away harmonic richness, smearing transients, and flattening dynamics.

For DJs who want to serve their audiences with both emotional depth and technical fidelity, it is essential to recognize that bad sound can originate from either stage in the production chain. Worse—and this is an underrecognized point—these two problems interact: a poor transfer, further degraded by compression, can make even the finest recordings unlistenable.

1.3 Historical Context

Before 2010, assembling a library of Argentine tango that had breadth, depth, and quality was nearly impossible. Even in Buenos Aires, high-quality CDs were hard to procure. Vendors’ stock was inconsistent, with the same tracks appearing across multiple releases in varying degrees of degradation. DJs trying to nourish young tango communities worldwide had few options.

Many turned to unauthorized digital distributions, such as the enormous and well-curated Tango Entropy collection that has circulated for at least 20 years in the former Soviet Union, Eastern bloc, and Europe. Others, particularly in the Americas, turned to the 40-CD Fiesta del Cuarenta collection curated by Mario Orlando, Osvaldo Natucci, Susanna Miller, and their associates. The tracks within these two collections were generally unavailable in lossless format, instead being distributed in heavily compressed condition. Since they originated from legacy CDs released before 2001, their tracks also featured transfer flaws, which ranged from minor to quite serious. All this was far from ideal, but in the early decades of the global tango renaissance while the revolution in computing had barely begun, necessity dictated compromise.

We live in a totally different world today, one where high-fidelity restorations offer a superior alternative. By starting with archival-quality analog sources and producing digital files free from unnecessary compression, these restorations deliver precise pitch calibration, refined equalization, and noise reduction. Restorationists do not always achieve perfection, and in some cases, their results fall short of pristine CDs. However, on average, the quality gains are substantial—and sometimes dramatic.

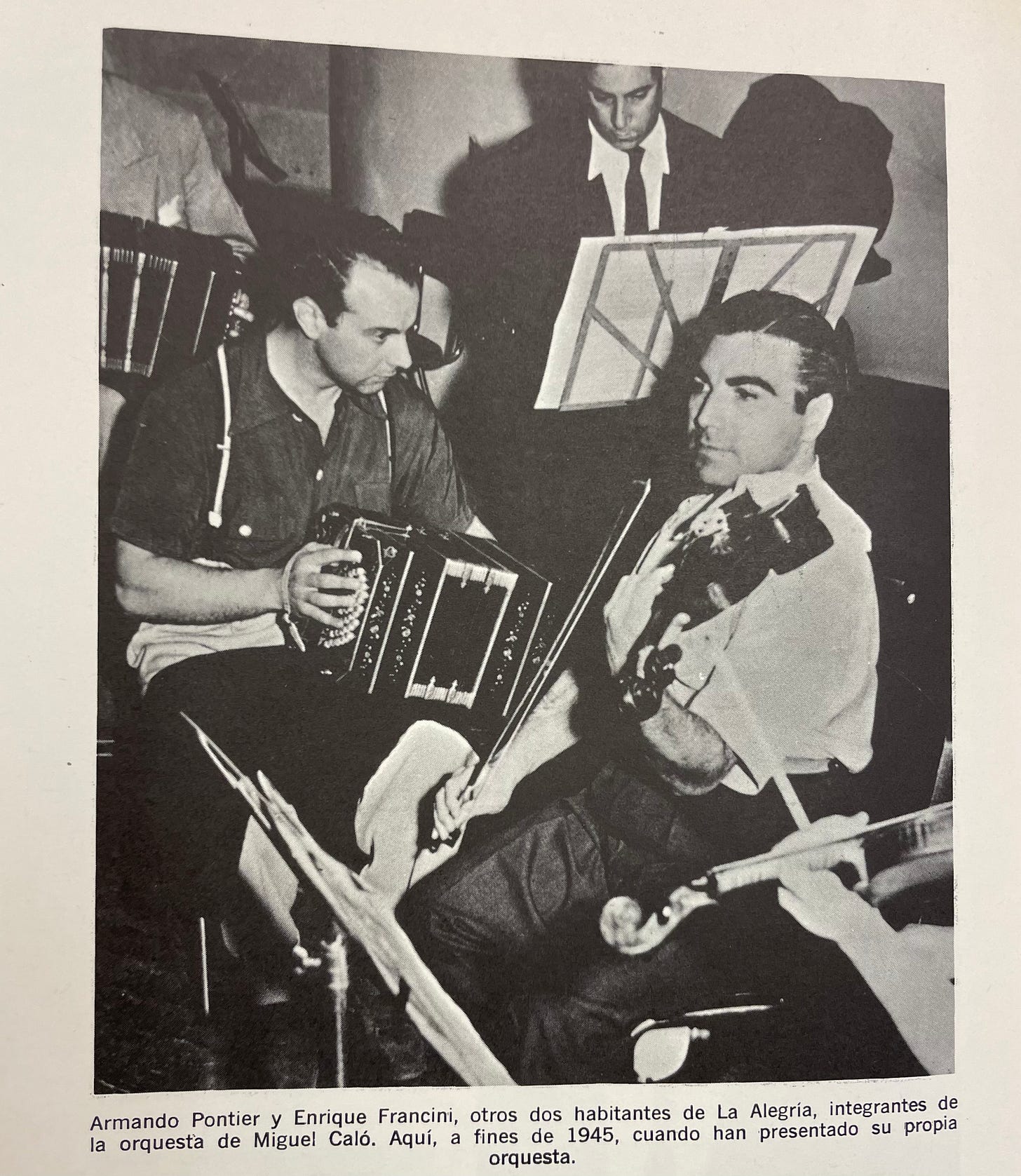

In my experience, the most striking improvements over legacy transfers are evident in the 1940s recordings of D’Arienzo, Troilo, Di Sarli, Pugliese, Caló, D’Agostino, De Angelis, Biagi, Laurenz, Demare, Rodríguez, Malerba, and García; the early 1950s output of Di Sarli and Troilo; and last but not least—and the 1930s works of Canaro, Donato, Fresedo, Di Sarli, and Orquesta Típica Victor. The improvements are not uniform within these orchestral releases—much work remains to be done. And as any devoted listener will realize, that list is not exhaustive. Better transfers are desperately needed for the 1940s output of Tanturi, Orquesta Típica Victor, Lomuto, and Francini-Pontier; the 1950s and 1960s output of De Angelis, Varela, Sassone, Gobbi, Maderna, and Salamanca; the 1935-39 output of D’Arienzo; and the 1920s output of Canaro, Fresedo, Lomuto, and other sextets.

Consequently, the best approach today for DJs curating an audio library is to combine uncompressed legacy tracks from CDs with the finest retransfers from modern restoration boutiques—a process that demands careful listening and sifting. This is a core aspect of the modern art of tango DJing.

1.4 Roadmap

This essay proceeds in five parts. Section 2 begins by examining the preservation of tango recordings, tracing the transfer from original analog masters to digital formats and identifying where degradation occurs. Section 3 breaks down the sources of transfer and compression artifacts in greater detail, zooming in on the current efforts of premier restorationists. Section 4 explains why restorations matter so much for dancers, and therefore, for event organizers. Section 5 concludes, urging DJs to seek out artifact-free transfers in high resolution.

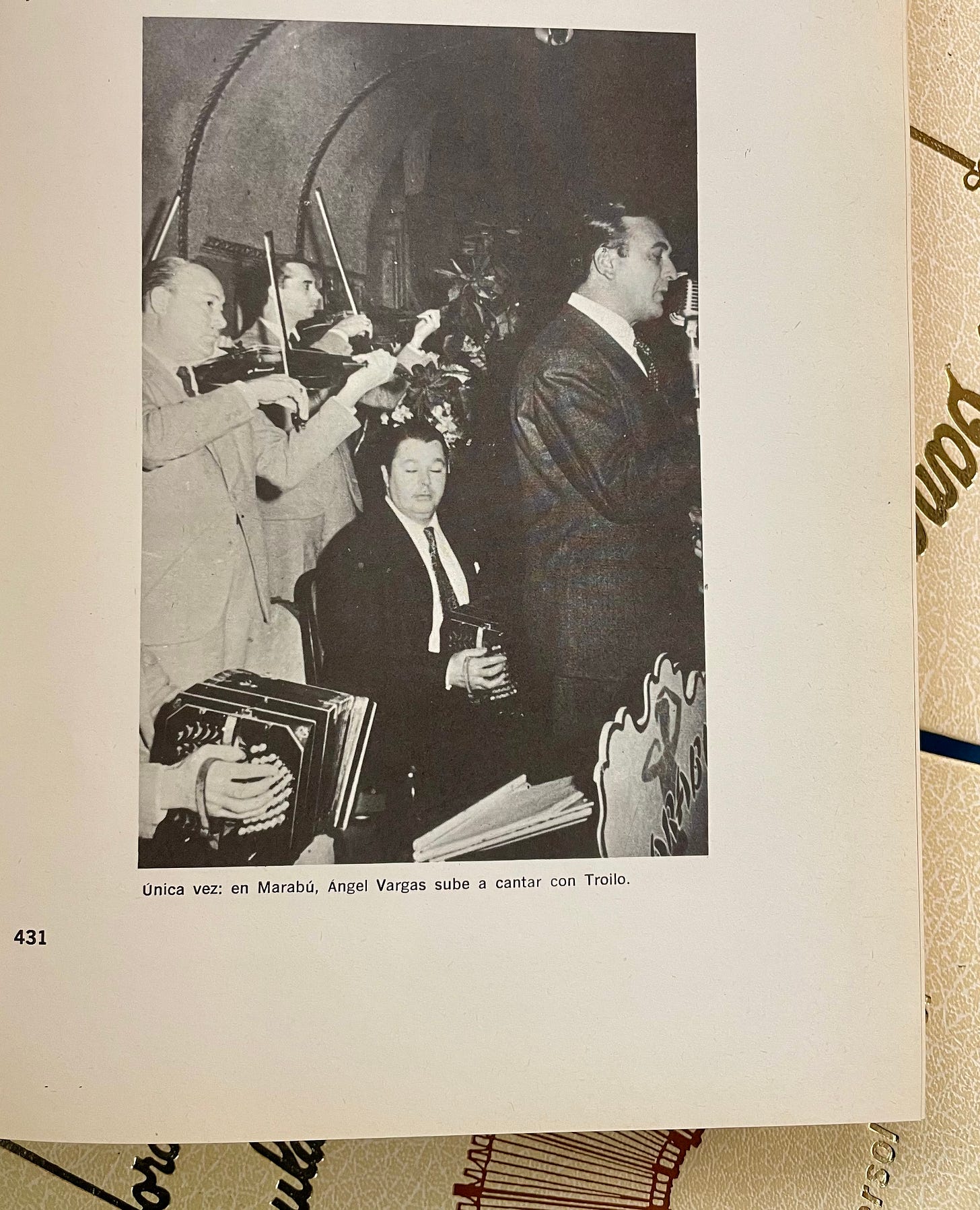

Photo: Ángel Vargas singing with Aníbal Troilo’s orchestra in Marabú after the singer’s 1947 departure from D’Agostino. From: Ferrer 1980.

Photo: Juan D’Arienzo conducting his orquesta típica ca. 1935-1940, from Ferrer 1980.

2. Context: the Production and Distribution of Tango

Understanding the production chain is essential to explaining the wide variation in the quality of tango recordings. Each stage—from the initial performance through various mastering techniques to modern digital transfers—affects the audio fidelity, making the selection of source material critical.

2.1 Mastering the Golden Age

Virtually all tango recordings derive from analog sources. In the earliest period, the mastering process employed a direct-to-disc method. Performances were inscribed onto a wax or lacquer surface using a cutting stylus that traced the sound’s waveform. The inherent properties of these materials—their softness and susceptibility to microscopic deformations—limited the range of frequencies that could be accurately captured. The resulting lacquer disc was electroplated to create a metal master, which then served as the negative for pressing shellac discs. The constraints imposed by the physical materials and groove geometry produced a distinctive sound profile that persists in transfers made from shellac.

The advent of magnetic reel-to-reel tape mastering in the 1950s represented a significant technical advancement. Sound was recorded as a magnetic imprint on tape coated with ferromagnetic particles in a polymer binder. The uniformity of these particles and the binder’s chemical stability were essential for achieving high fidelity. This technique expanded the dynamic range and reduced background noise relative to direct-to-disc recording. Strict control of tape speed and careful calibration of the bias—the alternating electrical signal used during recording—were necessary to encode the performance accurately. The tape masters produced by this process were subsequently used to create vinyl discs or other transfer media.

All analog media are subject to degradation over time. Shellac discs, due to their brittle composition, develop micro-fractures and surface erosion with each playback, leading to a gradual loss of detail. Although vinyl discs are more durable, they can still suffer from scratches, warping, and polymer degradation. Magnetic tapes, while not vulnerable to stylus-induced wear, are prone to issues such as oxide flaking, binder breakdown, and gradual signal loss from heat and humidity. The cumulative degradation inherent in these media often results in irreversible losses of sonic detail.

Metal, of course, is more durable. Yet its weight, size, and cost led record labels to favor recycling their metal masters after a few lucrative cycles of shellac production. Were it otherwise, we would be dancing today to crystal-clear recordings of late 1920s Lomuto, Fresedo, Canaro, De Caro, and Orquesta Típica Victor!

2.2 Mid-Century Transitions

A pivotal development in tango recording history was the mid-century shift from metal masters to magnetic tape masters. Driven by initiatives at RCA-Victor and prominent Argentine studios such as Estudios Odeon, T.K., and Music Hall, this transition was largely completed by the mid-1950s, with orchestras directed by Canaro, De Caro, Laurenz, Gobbi, Di Sarli, Troilo, Pugliese, D’Arienzo, Varela, Francini, Pontier, Salamanca, Federico, and Maderna, producing vivid recordings in unprecedented fidelity. Magnetic tape offered a broader dynamic range, reduced background noise, and the possibility of editing, thereby enhancing the fidelity of recorded performances.

During this transitional phase, at certain studios, certain metal masters were played back under tightly controlled conditions and recorded onto magnetic tape. This process required precise alignment of playback equipment and tape recorders, rigorous calibration of the playback heads, and optimization of frequency response settings to minimize distortions and mechanical noise. The quality of the resulting tape masters depended not only on the condition of the original metal masters but also on the technical accuracy of the transfer process. Properly stored tape masters suffered considerably less degradation than shellac discs, making them invaluable sources for restoration. Vinyls were pressed from these tape masters, offering a more durable format than shellac, albeit one with a quite different sound.

From the 1960s onward, the record labels began transferring recordings to vinyl, cassette, and later, CD. So did bootleg labels and distributors. In some instances, transfers were made directly from well-preserved masters. In others, engineers relied on chains of intermediate copies, a practice that compounded quality losses through pitch drift, mis-equalization, and a reduced dynamic range. Inconsistent sourcing decisions produced multiple versions of the same track, each with distinct audio characteristics. This legacy of retransfers complicates the modern pursuit of definitive digital editions of classic tango recordings. It can be very hard to find good renditions of important tangos, as a result.

The historical and technical context outlined above demonstrates that the current quality of tango recordings is the product of an analog production legacy, mid-century technological transitions, and varied reissue practices. Each production stage—from initial mastering and media degradation to the metal-to-tape transition and subsequent reissue inconsistencies—has left a lasting imprint on tango’s sonic character.

2.3 Can Restoration Really Recover the Subtle Stuff?

For restoration to be worthwhile, the original analog media must preserve enough transient energy and harmonic nuance—those delicate elements often lost in transfer, needle wear, environmental damange, and digital compression. Transients, the brief, high-energy onsets defining an instrument’s attack, are paramount in golden-age tango. They impart the crisp articulation of bandoneóns and the punch of piano chords that guide dancers through complex rhythmic passages. Recordings such as Orgullo Criollo, La Yumba, El Pollo Ricardo, El Amanecer, Mírame en la Cara, the milongas Flor de Montserrat and Señores, Yo Soy del Centro, and the valses Pobre Flor and Fibras illustrate these features vividly.

Although direct-to-disc recording and shellac pressing introduced distortion, metal masters produced with top-notch methods captured a surprising amount of detail. Some micro-details inevitably vanished during shellac production, but major transients and other subtle sonic characteristics survived. This matters because the human ear is highly attuned to the overall shape and energy of transients, even when fine-grained details are diminished.

Modern restoration approaches—particularly high-resolution digitization—have shown that these essential elements can indeed be retrieved. Tango Time Travel’s reissues of D’Arienzo, Laurenz, Demare, Fresedo, and Orquesta Típica Victor have uncovered, to a remarkable degree, many transients, harmonics, and dynamic shadings that were previously masked by legacy vinyl, cassette, and CD transfers. Similarly, Tango Tunes’ retransfers of Pugliese’s 1943–1950 recordings—from vinyl pressings originating in the “metal-to-tape” process—reveal that certain vinyl copies preserved more nuance than shellac discs alone could convey.

Safeguarding these core transients and harmonic architectures at a high resolution also makes them more robust to digital post-processing, including equalization, added reverberation, and even compression. This is critical and underappreciated contribution of the modern retransfer process.

For some doubters, however, the central question remains: can modern techniques reliably recover the finer sonic cues from the direct-to-disc era? There is no definitive answer based on solid empirical evidence. Still, a possible experimental design to address this would involve comparing the same recording under four conditions: (a) the original metal master; (b) a mint-condition shellac disc pressed from that master; (c) a typical shellac transfer that exhibits common transfer artifacts; and (d) the same as (c) after applying lossy compression, to simulate what is commonly found in bootleg libraries. Quantitative acoustic metrics would measure the retention of transient detail, while double-blind tests with dancers would gauge how well the rhythmic and dynamic nuances come across.

Needless to say, such a complex experiment (serving such a niche market) is unlikely to ever be done rigorously. Consequently, the better views on this subject will remain the province of informed opinion—and the best available evidence suggests that many original recordings contain enough vital sonic cues to justify ongoing restoration efforts. Further reasons for doing so will be discussed in the following sections.

2.4 The Era of Digital Compression in the Early Decades of Tango’s Renaissance

As tango expanded globally after 1983, performances and teaching began to spread beyond Argentina, taking root in cities like Paris, London, Amsterdam, New York, San Francisco, Tokyo, Rome, Moscow, and Los Angeles. With this growth came an urgent need to distribute music to a widening community of dancers and instructors. Carrying physical cassettes or CDs was impractical, and early laptops and external hard drives—typically offering only tens to hundreds of megabytes of storage—were heavily constrained. These limitations forced reliance on lossy audio compression formats in the MPEG standard throughout the 1990s.

Compression algorithms were designed to discard “inaudible” audio data to dramatically reduce file sizes, allowing users to store and share more music. In practice, however, these algorithms did more than remove extraneous noise—they stripped away subtle harmonic overtones, blurred transient details, and flattened dynamic contours. While this trade-off was initially unavoidable, its long-term impact on tango recordings was significant: many of the most widely circulated digital libraries of tango music—including those used in the global revival of the dance—were built on compressed, lower-fidelity files that masked the expressive nuances of the original recordings.

Even as hard drive capacities expanded into the gigabyte range by the early 2000s, compression remained dominant. The rise of file-sharing networks, such as Napster and later torrent platforms, entrenched lossy formats as the default, as bandwidth limitations, slow internet speeds, and storage costs continued to favor small, compressed files over lossless alternatives. This period of mass digital distribution ensured that much of the tango music traded across the world was encoded with significant sonic compromises. Today, these obsolete transfers riddle the landscape of Spotify and Apple Music, streamed and sold in most cases by unauthorized bootleggers rather than record labels and restorationists.

The legacy of this era persists. Many tango DJs—knowingly or not—play compressed versions of recordings whose dynamic depth has been dulled by the interaction of decades-old transfer artifacts plus compression. The result is that much of tango’s richness has remained obscured.

2.5 The Pursuit of Fidelity Through Modern Restoration Methods

Modern restoration efforts address these challenges by starting with the cleanest surviving analog sources and bypassing the flawed intermediate transfers that have long haunted tango. The quality gains can be dramatic, restoring much of the musical vitality that earlier processes compromised. We are now ready to examine that process in greater detail.

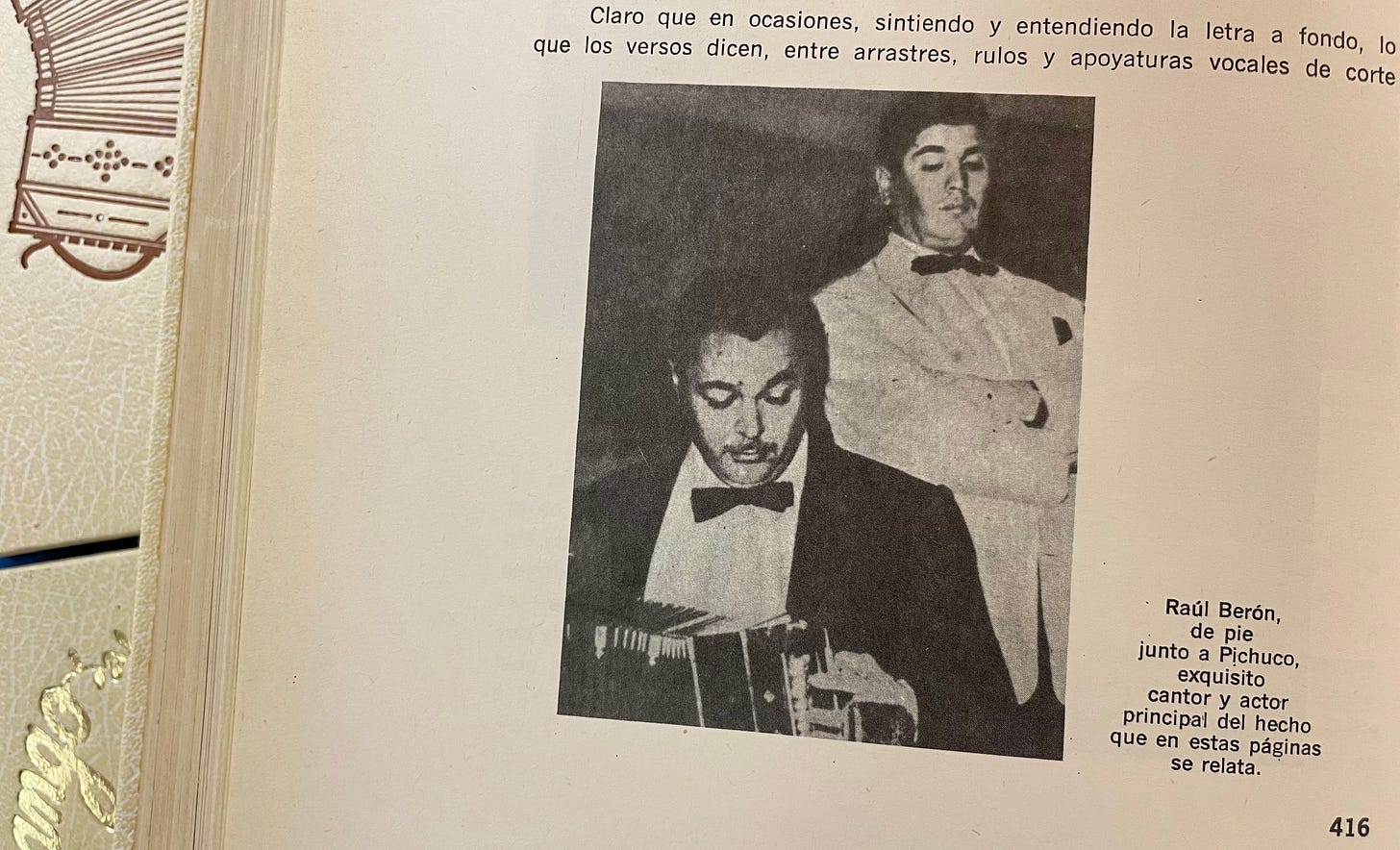

Photo: The duo of Raúl Berón and Aníbal Troilo, ca. 1951-1955, from Ferrer 1980.

Photo: Pedro Laurenz serenading a relative, from Ferrer 1980.

Photo: Tango Time Travel > Method by Jens-Ingo Brodesser.

3. Restoration: Modern Techniques

This section outlines the techniques and source-selection strategies employed by today’s tango restorationists.

3.1 Source Selection

High-quality digital transfers begin with identifying and obtaining access to the best possible analog sources. Without pristine originals, any restoration—even with modern tools—risks compounding flaws through poor transfers or compression. Organizations such as Tango Tunes and Tango Time Travel collaborate with collectors, estate sales, and private archives in Buenos Aires and Montevideo to locate and digitize top-quality recordings. Collectors across the globe—including Akihito Baba and Yoshihiro Oiwa from Japan, Keith Elshaw from Canada, Frank Jin from China, Christian Xell from Austria, and Bénédicte Beauloye and Jens-Ingo Brodesser from Belgium—have played key roles in finding high-grade discs.

Recent restoration techniques rely on comparing multiple discs of the same track to neutralize defects unique to each copy. By aligning and blending uncorrelated flaws, restorationists achieve far clearer results than methods used in the 1990s and 2000s, when they typically transferred only a single disc meeting minimal standards. Shellac and vinyl both degrade in distinct ways—shellac’s grooves wear down from repeated stylus contact, while vinyl accumulates micro-abrasions or warping due to heat, humidity, and poor storage. In earlier decades, depending on a single damaged disc amplified imperfections at every stage of reproduction.

Some recordings survived on metal masters, which were later copied to magnetic tape in the early 1950s. After these masters were destroyed or lost, the tape copies were preserved by rights holders who acquired them when record labels closed or reorganized. Their condition now varies, with certain tapes remarkably intact and others compromised by environmental harm.

An emerging priority is to track down vinyl records pressed from the 1950s metal-to-tape process. These often exhibit improved fidelity, making them prized sources for digital transfers. Over time, the hunt for first-instance tape masters may overshadow the pursuit of rare shellacs, yielding a new wave of clearer, higher-fidelity restorations.

Practical challenges abound when gathering fragile artifacts like these. Shellacs and vinyls are painstakingly sourced from estate sales, packed carefully, and sometimes transported only a few dozen at a time by plane to avoid damage. Many are processed where they are found. Over the coming decades, continued discoveries of magnetic tape masters and superior early pressings promise to recover sonic details previously lost, improving the sound of tango for modern audiences.

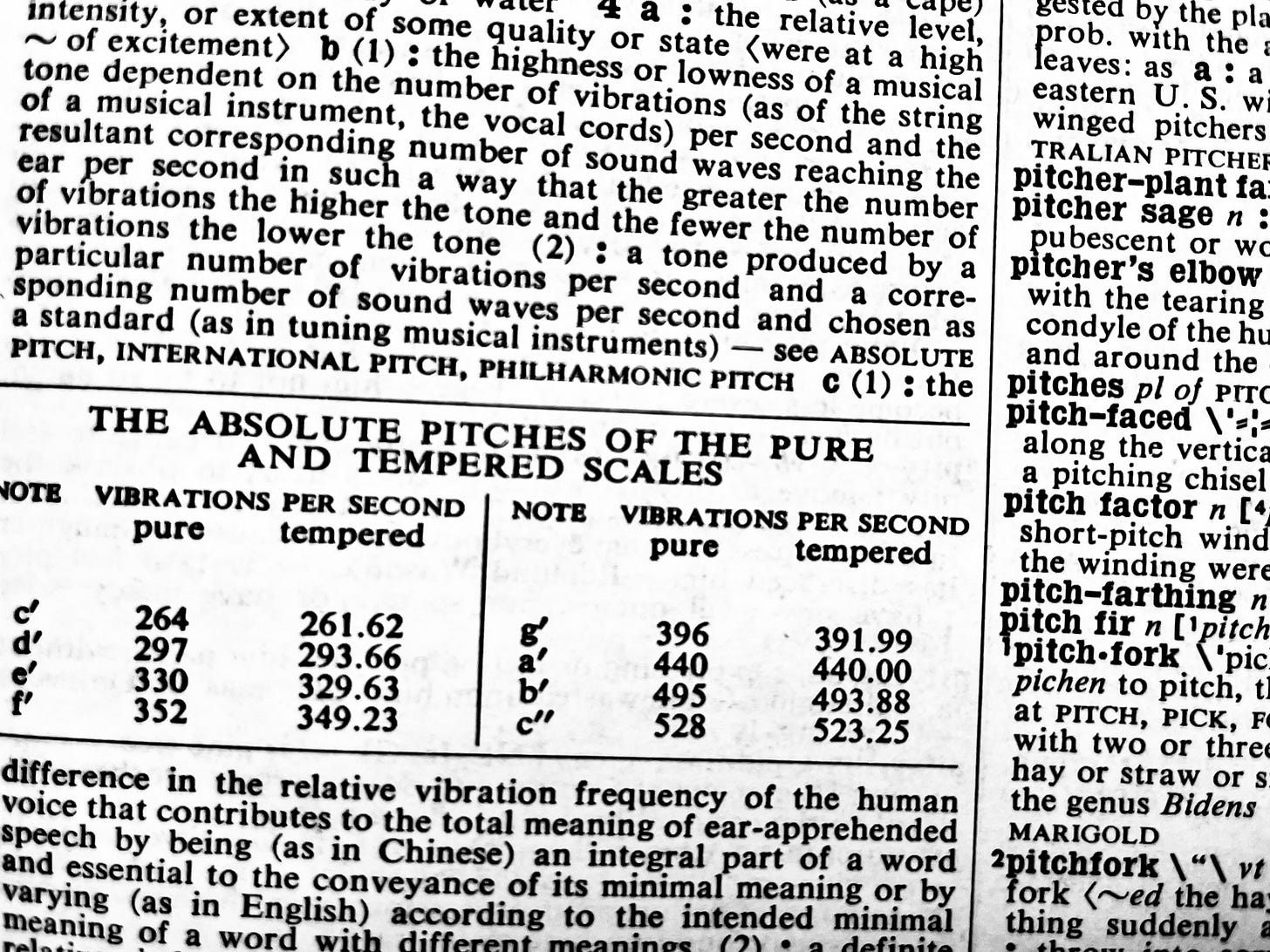

Photo: Merriam-Webster’s New International Dictionary. 3rd ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 1981.

3.2. Pitch Accuracy: The Foundation of Musical Integrity

Pitch is the cornerstone of tango’s musical identity. Early transfers were prone to subtle pitch drift—often deviations of just a few cents—caused by mechanical instabilities, variable platter speeds, and inadvertent or deliberate tempo alterations. These issues shifted orchestral tuning away from historically accurate standards (A = 435 Hz to A = 442 Hz), thereby altering the performance’s impact. Mechanical distortions and tracking inaccuracies compounded the problem, resulting in recordings that can sound noticeably flat or strained.

In many modern restorations, the approach to pitch correction remains a largely manual process. Experienced restorationists perform fundamental instrumental analysis and rely heavily on careful listening and by-hand adjustments to detect even minor pitch deviations. Using calibrated reference tones and simple measurement tools, they scrutinize each track to identify discrepancies in tuning. While advanced digital signal processing techniques exist, much of this work presently appears to be executed “by ear,” guided by a deep understanding of historical tuning practices and the performance’s intended sonic character. Once discrepancies are identified, restorationists manually recalibrate the pitch, ensuring that the analog transfer adheres precisely to its original standard.

Without such manual recalibration, the cumulative effect of pitch inaccuracies disrupts the harmonic coherence and timbral balance of the music. These issues are particularly disturbing to the ear in older transfers Di Sarli, Troilo, De Angelis, Laurenz, D’Arienzo, and Biagi, whose recordings, originally pressed on vinyl, cassette, and CD, have often migrated into bootleg tango libraries with their pitch errors intact. Through careful, hands-on pitch correction, restorers preserve the authentic character of tango, ensuring that every note resonates with the intended emotion and energy for today’s pista.

3.3. Equalization and Preamplification: Restoring Balance

Before standardized curves like the RIAA became universal, record labels employed proprietary pre-emphasis techniques during recording. Because analog media—such as shellac and vinyl—are limited in dynamic range and physical space, engineers boosted high frequencies during the recording process to overcome inherent noise and groove limitations. This “pre-emphasis” allowed the signal to be recorded with a higher signal-to-noise ratio, effectively masking some of the medium’s imperfections. On playback, a corresponding “de-emphasis” curve was required to restore the original tonal balance, reducing the previously boosted treble and re-establishing equilibrium across the frequency spectrum.

In legacy transfers, generic or mismatched equalization often resulted in tonal imbalances: bass could become bloated, treble harsh, and the midrange unnaturally hollow. Such distortions not only obscured the music’s intrinsic qualities but also compounded other transfer flaws.

Modern restorers, however, leverage label-specific preamplification curves to precisely reverse the original pre-emphasis. By applying the correct de-emphasis, they recover the authentic timbral richness intended by the original engineers. This careful equalization—applied during the analog-to-digital transfer—ensures that the distinctive sonic character of tango is preserved, independent of subsequent digital processing. The restoration process, therefore, addresses issues rooted in the original analog medium, offering a correction that separates genuine musical nuance from distortions introduced during legacy transfer efforts.

3.4. Mechanical Artifacts: Wow, Flutter, and Stability

Older recordings often suffer from wow and flutter, speed fluctuations introduced by inconsistencies in recording lathes, playback motors, or even warped shellac discs. These variations distort sustained notes—particularly noticeable in bandoneons and violins—causing an unnatural pitch wobble that warps the music. Many bootleg transfers ignored these flaws, leaving tracks riddled with subtle but persistent instabilities. Arguably, recordings by the orchestras of Laurenz, Di Sarli, Troilo, Demare, and D’Arienzo suffer the most—but the problem is widespread in legacy transfers, rendering many of them unplayable. Modern restoration techniques use software-based pitch stabilization and mechanically optimized playback systems to correct these fluctuations, restoring the intended timing and tonal purity. With these improvements, rhythmic precision is preserved, allowing dancers to connect more intuitively to the music—enhancing both musical immersion and the ability to dance fluidly over extended sets.

Photo: Francisco Fiorentino and Orlando Goñi accompanying Aníbal Troilo in a recording session ca. 1940-1944, from Ferrer 1980.

3.5. Reverberation: The Case Against “Locked-In” Spatial Effects

Reverberation is the natural persistence of sound in a space, creating ambience and depth. In recordings, reverberation can be introduced with physical or digital instruments to evoke a particular atmosphere or to simulate the acoustics of a concert hall, wood-paneled chamber, or virtually any other space. The possibilities are infinite. However, when reverberation is “baked in” during the analog mastering process, particularly with legacy transfers from shellac discs, it can distort the music in several critical ways.

Shellac discs are especially prone to mechanical noise and groove wear. When these inherent imperfections are combined with fixed, analog reverb—applied by engineers often working with limited technology from three or five decades ago—the result is an irreversible layering of spatial effects. Such reverb does more than simply add ambience; it indiscriminately amplifies existing flaws. Transient details become blurred, the fine articulation of instruments is masked, and the overall clarity of the performance suffers. Moreover, when these recordings are subsequently subjected to lossy compression, the distortion compounds: compression algorithms tend to flatten dynamic range and obscure subtle nuances, further muddling the already “locked-in” reverb. This double degradation—first from the analog reverb’s inability to discriminate between signal and noise, and then from the compression’s reduction of fidelity—can significantly distort the intended sonic texture.

Modern restoration techniques sidestep these pitfalls by capturing the pure signal directly from high-quality analog sources and postponing the application of reverb. This approach allows for digital reverb to be applied dynamically at the point of playback, tailored to the specific acoustics of the venue and the atmosphere the DJ wishes to create. By separating intrinsic audio quality from spatial enhancement, restorers can preserve the integrity of transients and maintain the delicate balance of tone and clarity that is key for hearing tango in high fidelity.

Photo: Merriam-Webster’s 1981.

3.6. Higher-Resolution Formats

3.6.1 Lossless and Uncompressd Formats Versus the Alternatives

High-resolution audio, with its enhanced sampling rates and bit depth, preserves every nuance of tango’s original performances. When a high-quality analog transfer is stored in lossless formats such as FLAC, WAV, AIFF, or ALAC, its full sonic texture—from the chats between piano, strings, and singers to the natural decay of a bandoneón’s bellows—is maintained with high fidelity. In contrast, lossy compression formats in the MPEG or AAC standard rely on psychoacoustic models that discard data deemed “inaudible,” inadvertently deleting or effacing subtle details essential for tango’s expressive depth. These compression artifacts flatten dynamics, smear transients, and erode harmonic overtones, dulling the emotional impact of tango for dancers.

Compression is especially detrimental when applied to tracks derived from pre-1950 shellac transfers. Shellac discs, created as near-exact imprints of metal masters, capture every minute sonic detail but also bear the scars of their fragile medium—noise floors, surface irregularities, and inherent mechanical distortions. The psychoacoustic assumptions underlying lossy algorithms are calibrated for modern recordings with relatively clean signal-to-noise ratios; when applied to these aged, noise-laden transfers, the compression process often exacerbates existing imperfections. Instead of merely reducing file size, the algorithm aggressively eliminates nuances that are already marginal, further muddying transients and reducing the dynamic contrast that gives tango its vitality.

For DJs and organizers dedicated to preserving tango’s artistic legacy, it is critical to recognize that even the highest-quality analog transfers can be undermined by subsequent lossy encoding. In an era defined by rapid solid-state drives and expansive modern memory architectures, lossless, high-resolution audio is no longer a luxury—it is the obvious choice. Yet, a natural question arises: does compression really matter in terms of perceptual experience? Do listeners—beyond audio engineers and preservationists—actually perceive a meaningful difference between lossy and lossless formats?

3.6.2 Does Compression Really Matter?

I have encountered at least one tango DJ who argues that if a one begins with a “clean” shellac transfer of a golden‐age orquesta típica—one that, as is customary, exhibits a steep high-frequency roll-off above 8–10 kHz—then further lossy compression is inconsequential.

I find this argument unpersuasive. Even within such a constrained bandwidth, the subtle degradations in transient response and harmonic detail introduced by lossy encoding can significantly erode audio fidelity. This is particularly critical in historical recordings where every nuance carries artistic and cultural weight. Although controlled listening studies in this musical genre are conspicuously absent, one can envision an experimental design that compares listener ratings of lossy versus uncompressed formats across various quantitative dimensions.

My prior belief, grounded in a lifetime of tango listening and two decades of dancing, is that lossy compression results in serious degradation. In statistical terms, if we were to construct a likelihood function based on perceptual differences across a sample of listeners, it would be heavily influenced by what we might call “tail-area listeners.” These are the milongueros, musicalizers, and audiophiles—individuals with hyper-sensitive ears for tango who have developed a deep feel for the canon of the genre. They are responsive to even minute losses in transient sharpness and harmonic richness. Their assessments, though perhaps representing a minority, would shift the posterior joint density of the listening ratings markedly, revealing differences that a mere null hypothesis test might obscure.

The significance of this group extends beyond their perceptual acuity and outlier status. Tail-area listeners are often tastemakers—deeply engaged in tango communities, highly attuned to the genre’s nuances, and frequently sought after as dancers, DJs, or professionals. Their preferences are not the only ones that matter, but their refined perceptions carry outsized influence, shaping musical selections and guiding broader trends in the market for events and DJs.

What that means is that even if a one-shot gold-standard experiment showed no detectable degradation under compression, it could still be the case that compressed audio files are believed to sound worse “in the wild” because of the opinion leadership of sensitive listeners occupying nodal positions in networks of dancers (i.e., tastemakers).

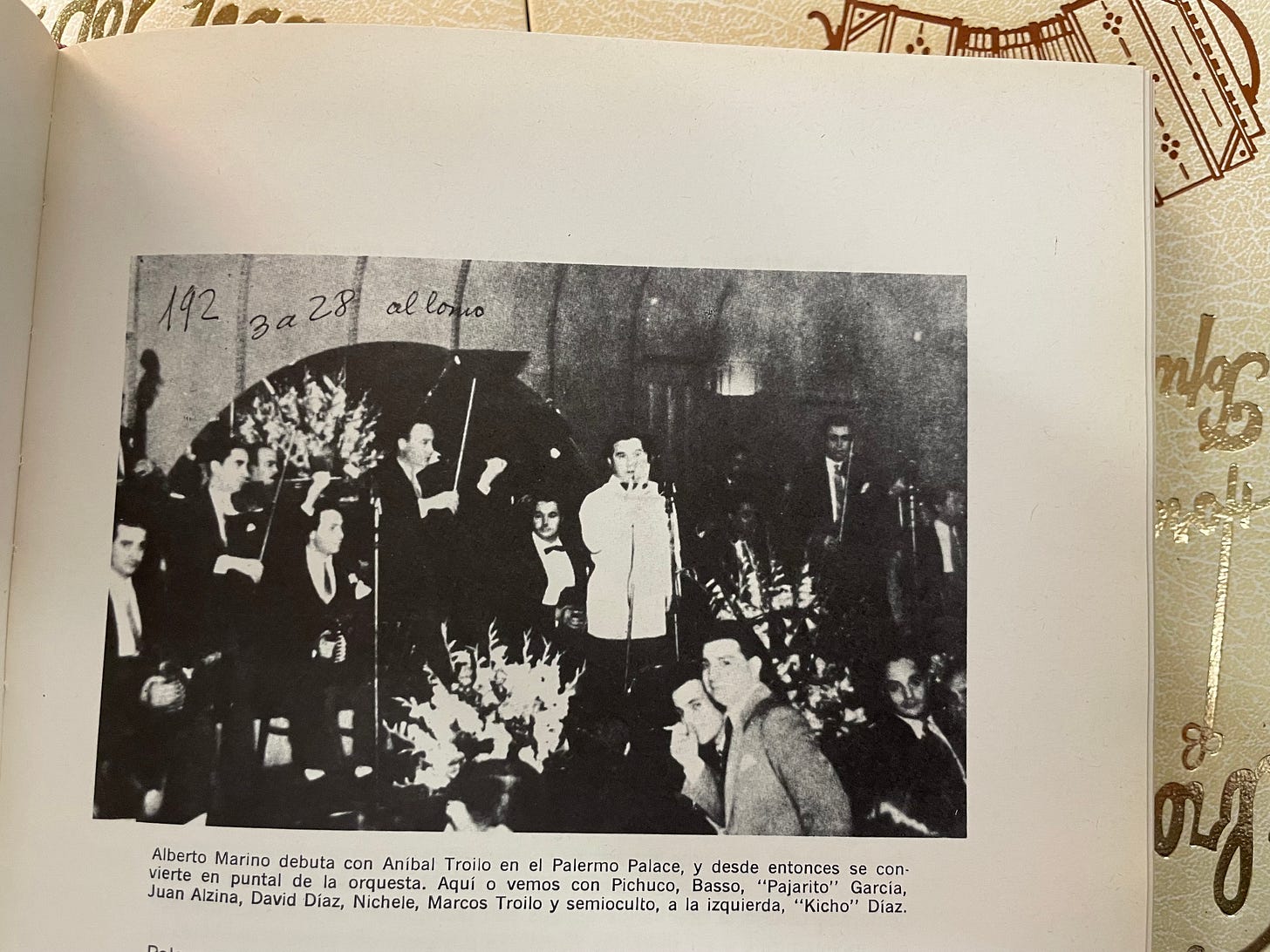

Photo: The debut of Alberto Marino with Aníbal Troilo’s orquesta típica in 1943, from Ferrer 1980.

4. Implications: Why It Matters

Dancers react to sound with a visceral immediacy, often unaware of the subtle degradation that accrues over a long evening. Over the course of a three- to seven-hour milonga, the relentless burden of low-fidelity music imposes both physical strain and psychological weariness. This essay has examined two distinct yet intertwined problems—poor analog transfers and lossy compression. While it is challenging to isolate one as more impactful, their interaction creates a compounding effect.

Lossy compression at bitrates of 256 kbps or lower distorts the music’s inherent clarity. Transients become blurred, dynamics are compressed, and critical harmonic overtones along with microtiming nuances vanish. The result is a soundscape that leaves dancers feeling unmoored and increasingly fatigued as the evening goes on. Equally important is the issue of transfer quality. When recordings suffer from off-pitch calibrations, bad equalization, mechanical artifacts, or overzealous reverb, the musical narrative falters.

The ramifications extend beyond mere technical shortcomings. They deplete the dance floor of its energy and cause dancers—especially new ones—to quit tango, believing incorrectly that the music just sounds weird. It’s akin to stepping into a gourmet restaurant where the chef’s signature dish has been replaced by a second-rate imitation—newcomers judge the entire cuisine by that poor experience and never return. Over the past twenty years, I have personally witnessed this underappreciated phenomenon numerous times. Indeed, bad bootlegs do sound weird.

Beyond this, there are tangible business consequences. Dancers rarely voice direct complaints about audio quality, yet lingering dissatisfaction discourages them from returning. A milonga thrives on the synergy between music, dancers, and ambiance. When this feedback loop breaks—partners disconnecting by the third song of the tanda, the ronda disintegrating, leaders sitting out the first two songs, and so forth—the room’s collective spirit collapses. Even dedicated listeners lose interest, leaving event organizers to deal with dwindling attendance and a subdued atmosphere. Of course, other things matter—charisma in the room, music selection, refreshments, the floor and ventilation system—but this is a big one.

In stark contrast, high-fidelity restorations preserve every nuance of the original performance. Modern transfers that maintain crisp transients, expansive dynamic range, and precise microtiming rejuvenate the dance floor with an authenticity that can be palpably felt. The proof of this lies clearly in the outstanding retransfers of—to name just a few quite striking examples—Troilo with Fiorentino and Marino, De Angelis with Dante and Ruiz, D’Arieno with Mauré, Echagüe, and Laborde, Pugliese with Chanel and Morán, Laurenz with Podestá, Biagi with Ibañez and Ortiz, and Demare with Berón and Quintana.

For DJs and tango music collectors, using high-resolution, lossless libraries is essential to supporting dancers. It also plays a critical role in preserving the soul of tango for future generations. Analog media—shellac, vinyl, and tape—deteriorates over time, and with each passing day, these collections face irreversible degradation.

Photo: Enrique Francini and Armando Pontier in a recording session with the orquesta típica directed by Miguel Caló ca. 1942-1945, from Ferrer 1980.

5. Conclusion

Modern high-fidelity restorations have set a new baseline for tango sound, addressing both transfer artifacts and the distortions imposed by lossy compression. By sourcing the cleanest available analog masters, applying precision restoration techniques, and preserving the results in high-resolution formats, a large part of tango’s original sonic character has been recovered. The impact is not subtle. Properly restored recordings preserve orchestral dynamics, stabilize pitch, and restore timbral balance, allowing the true texture of the music to emerge with more clarity and force than ever before. Moreover, this work is far from over, and the next frontier might be the hunt for tape masters made in the 1950s from metal masters in the RCA Victor and Odeon vaults.

Despite optimistic claims to the contrary, lossy compression can also be a significant problem for pre-1950 shellac transfers. Aggressive compression based on psychoacoustic models designed for modern recordings strips away not just redundant data but vital harmonic information, smearing transients and collapsing the spatial depth that gives each performance its distinct character. Golden age tango does not handle it well. The result is a reduction in fidelity and a fundamental distortion of the music’s feel—one that decisively alters how dancers perceive and respond to the sound over the duration of a typical milonga or practica.

For DJs, the choice is straightforward: upgrade. For organizers, the responsibility is equally clear: nudge DJs to do so. The difference is clear—and indeed, clearest to the most experienced and knowledgable listeners.

Acknowledgements: This essay has benefited from the insights of affiliates of the Tango Time Travel and Tango Tunes restoration projects, as well as Frank Jin, Daria Nikolaeva, Howoon Chung, Jun Yi, Iskra Strateva, Vadim Vasilenko, Tom Lee, Dante Polichetti, and Bazyli Ćwiartek.

© 2025 Barry Hashimoto. All rights reserved. Proprietary images and text may not be reproduced, distributed, or used in any form without the author’s permission.